|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

A decade ago this year, Michael Jackson died. Two days after his death on June 25, 2009, I wrote the following tribute for The Charlotte Observer. Michael Jackson may have done unspeakable things to children, but as is the case with so many artists, those things, as horrible and damaging as they are, don’t erase his art. We’ve seen a number of artists go down in blazes of controversy since the #MeToo movement began raising greater awareness of the scope of abuse. And those artists have deserved what they’ve gotten. Still, for me, Michael Jackson will forever be a difficult subject. He was my first musical hero. He was deeply troubled. He disappointed me profoundly (after all, I had my own childhood #MeToo experience). And yet, I will always feel a deep love for him — and a deeper empathy for those he hurt.

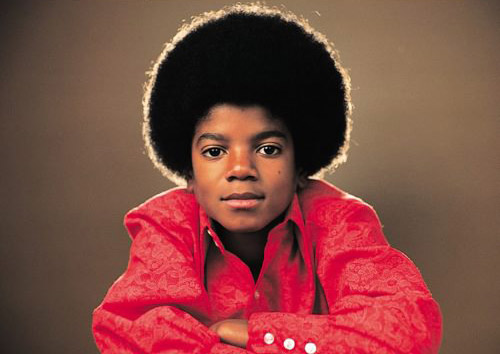

The pop singer as a young man

Michael Jackson bridged a gap between Black and white audiences, first in the ’70s, then the ’80s. His musical mark is clear, but his life… not so much

By Mark Kemp, The Charlotte Observer, June 27, 2009

Michael Jackson was a beautiful boy. Too bad he never saw it that way. But in remembering his music and life on Thursday, the first image that came to my mind was that of an innocent 13-year-old singing the bittersweet ballad “Ben” on the Sonny & Cher show: “Ben, most people would turn you away. I don’t listen to a word they say,” he sang, standing in a stylish orange suit before a huge backdrop bearing his name, his big Afro framing delicate features. “They don’t see you as I do. I wish they would try to.”

I think of the poster I had on my wall of Michael when he and I both were around 11. I wanted to be just like him. I think of my first concert, at age 12: The Jackson 5 at the Greensboro Coliseum in 1972.

Michael Jackson broke musical and racial boundaries long before “Thriller” made it onto MTV in the 1980s. In Greensboro, my friend Robert and I were two of the few white kids sprinkled like grains of salt in the largely African American audience. Schools across the Carolinas had just begun to integrate after years of fierce battles, and the Jacksons helped bring us together. The white kids and new Black kids at my elementary school giddily sang along to every word of “I Want You Back” and “ABC” together, not separately.

He continued to break down musical and racial barriers when he and his music brought young Black kids and young white kids together again in the ’80s with his iconic dance moves and burning mix of rock and funk in songs such as “Billie Jean” and “Beat It.”

But as healing as Jackson’s music was, his personal life was filled with sadness and tragedy. He never had a childhood. His father, by all accounts, was a cruel and dictatorial stage dad. He also never had a private life. People hounded him for what he was, not who he was. He wanted so badly to be somebody else that he radically altered his appearance.

It broke my heart when, as the music editor of Rolling Stone in 1997, I received a book that detailed the sexual abuse allegations he’d settled a few years earlier. We chose not to run a story at the time, because the book’s legitimacy was questioned.

No one but the people who were involved knows what happened between Jackson and the children he invited into his home. (UPDATE: Later developments have brought more legitimacy to the accusations.) What we do know is that his remarkable body of work is as important to popular music as that of Sinatra or Elvis.

Jackson’s songs bring people together. He combined numerous pop styles into sparkling productions that appeal to almost everybody and influenced generations of newcomers, from Justin Timberlake’s mainstream pop to Kanye’s hip-hop, Usher’s contemporary R& B, Lenny Kravitz’s rock, and Felix da Housecat’s electronic dance music. Jackson’s groundbreaking videos laid the foundation for everything we see on MTV today. His dance moves have been adapted by pop stars from Britney to Beyoncé. But most important, his music has made millions of people across the globe very happy.

When news of his death hit Facebook on Thursday afternoon, everybody had something to say: He was a genius. He was a child molester. He was a freak. He was an icon.

All I could think of was that beautiful boy singing “ Ben.”

The Charlotte Observer, June 27, 2009

he never did anything to boys, the court ruled that he’s innocent, plus the fact that there’s no evidence to prove that. The people who accused him JUST WANTED HIS MONEY!!!!!

RIP Michael