“The city of Fez lies below, very slowly disengaging itself from the morning mist and smoke, while a million cocks crow at once.” — Paul Bowles in Morocco

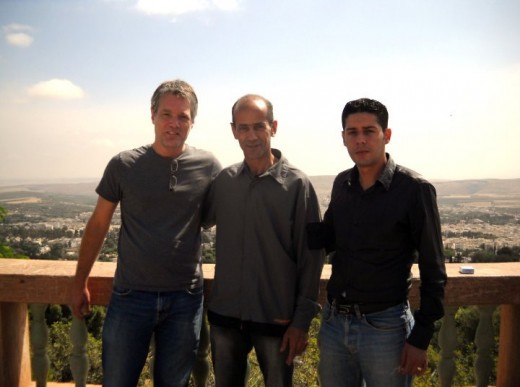

“You take a picture here, Mark — look!” Maurat Charef is standing with me on a terrace high above the city of Sefrou, some thirty kilometers southeast of Fez in the foothills of Morocco’s Middle Atlas mountains, dramatically panning his hand across sprawling clusters of white homes set into the rolling yellow-brown landscape. The sun is beating down on us, but it’s not oppressively hot in early June 2010; a breeze smiles its way between us.

Dressed in faded blue jeans and a starched black collar shirt, Maurat, a handsome young accountant in his late twenties with a head full of coal-black hair, speaks very little English and I virtually no Arabic or French. But we manage to communicate through cognate words and exaggerated gestures. He and his fifty-year-old friend Mohammed Barqine, a thin, balding man who waits tables back at my hotel in Fez, have agreed to drive me and a fellow journalist, Betto Arcos, through the nearby countryside and play some of the CDs they listen to when American reporters aren’t around. I have come to Morocco to cover the Fez Festival of World Sacred Music for Rolling Stone, but today Betto and I are taking a few hours off from the whir of live performances to get a little real-life context.

Before we stopped to take in this spectacular vista, we were riding in Maurat’s battered gray Mercedes listening to the car’s malfunctioning stereo play an endless loop of a song by singer Said Sanhaji. He performs a blend of traditional Moroccan music and pop known as chaabi and is similar to the Algerian rai made famous in the West when Cheb Mami sang on Sting’s 1999 hit “Desert Rose.” Maurat and Mohammed either did not notice or didn’t care that the same fragment of a song had been wailing away for a good half-hour. But Betto, a radio journalist with a discerning ear, took heed of the looped music; he turned to me at one point during the drive from Fez to Sefrou, and with a roll of his eyes, shrugged. After all, we are at the mercy of our gracious hosts, who will take us to several other nearby towns and cities over the next twelve hours. In addition to Sefrou, we’ll travel through Azrou, to the south, and Meknes, to the west, as well as the tiny villages of Bhalil, where people live in hillside troglodyte cave homes, and Ifrane, whose alpine villa-style houses, steep mountains and crisp air offer a stark contrast to the rest of Morocco. Ifrane is more Switzerland than North Africa.

For its part, Sefrou was once home to as many as 6,000 Jews, and while some still live here, most left Morocco in the aftermath of Israel’s Six-Day War in 1967. Mohammed, whose English is much better than Maurat’s, likes to tout Morocco’s comparative tolerance in this part of the world. “Here, no problem between Jews and Muslims,” he tells us. “They give a lot to the Moroccan people. They are generous; they are good.”

It is this atmosphere of openness that has brought Western lovers of the world’s great music traditions to Morocco every summer for the past sixteen years. You could say this pilgrimage began nearly three decades before that, in 1968, when the Rolling Stones’ late guitarist Brian Jones hooked up with a group of musicians in the village of Jajouka — northwest of Fez, toward Tangier — to record what may be the first popular album of world music, Brian Jones Presents the Pipes of Pan at Joujouka. On this hazy June morning, we are about midway through the 2010 Fez Festival — a ten-day, jam-packed journey into the sounds of artists not just from Morocco, but also places as far flung as Cambodia, Mongolia, India, Egypt, Iran, Afghanistan, Syria, Turkey, Tunisia and Burundi. During a performance earlier in the week by Tanzania’s Rajab Suleiman Qanun Trio, one of the ensemble’s songs segued into the deep, throaty sound of a muezzin calling Muslims to prayer from the top of a nearby mosque. The group paused until the call, or adhan, was finished.

Fes Festival: Shakila and Rajab Suleiman Trio from Michal Shapiro on Vimeo.

Later in the week we’ll see a band of Jews from Baghdad perform a mix of ancient Iraqi and Jewish Arabic folk songs. But it’s the Moroccan music that dominates the festival’s sixty shows, from the songs of feminist pop singer Najat Aatabou (who was once sampled by the British electronica duo Chemical Brothers) and rap group the Fez City Clan to the contemporary classical and chamber music of a Schoenberg-influenced composer and a variety of sounds from Sufi singers including, perhaps surprisingly, an all-female group.

Artists from the U.S. have not gone unnoticed here. Although singer/songwriter Ben Harper canceled at the last minute (due to a skateboarding accident!), the American jazz men David Murray and Archie Shepp and gospel singers the Blind Boys of Alabama have made the trip with their limbs intact and their hearts and minds wide open. The Blind Boys’ drummer, Ricky McKinnie, would later tell me during the group’s afternoon sound check at the magnificent Bab Makina amphitheater that Fez has a special meaning to his group. “The main problem with the world today is that we don’t understand one another,” McKinnie would say, sitting in a straight-back chair in the middle of the theater flanked by its massive, castellated, ochre-yellow walls and towers. “But if you can come up to a place where you can meet and have a central ground, things will always work out. Through music you can communicate, and it doesn’t matter who you are or where you come from.”

“The main problem with the world today is that we don’t understand one another.”

This year marks the Blind Boys’ second appearance at Fez; their first was ten years ago, when young Moroccans went bananas over the septuagenarian vocal group’s husky harmonies and frisky mix of gospel, rock and rhythm and blues. McKinnie would lean closer to me during our conversation, his voice becoming a half-whisper as he invoked the deity that he looks to for spiritual fulfillment: “You know, Jesus said, ‘If I be lifted up from the earth, I will draw all men unto me.’ I think he’s doing what he said he would do — drawing people from everywhere.”

DRAWING PEOPLE from across the globe to a place of mutual understanding was the goal when Moroccan anthropologist Faouzi Skali — whose specialty is the mystic Sufi branch of Islam — founded the Fez Festival in 1994. His vision was idealistic and plan ambitious: He wanted to do something that would change the world, or least change peoples’ perceptions of the world’s various cultures and customs. He was troubled by things that were being written and said about Islam following the first Gulf War. He also foresaw the exponential growth of globalization. “From 1991,” he has said, “it was clear to me that we were entering a new era where cultures would play a key role in realpolitik.”

Skali, who broke with the Fez Festival three years ago to found the Festival of Sufi Culture, chose to hold the event in the 1,200-year-old city of Fez for several reasons, including its historic support of the arts, its academic renown, and its peaceful coexistence of Muslims with the country’s tiny Jewish and Christian communities. In addition to being Morocco’s original capital and its third largest city (behind Casablanca and current capital Rabat), Fez has what’s believed to be the world’s largest still-functioning medieval-period medina, with a labyrinth of some 9,000 narrow streets and alleyways, and no cars. Skali’s idea was to present a forum, in a city rich with world history, for intellectuals to discuss and debate modern-day global issues ranging from the Israeli-Palestinian conflict to the characterization of countries as either “developing” or “developed” to the roles of science and spirituality in global affairs. During mornings, panels of writers and thinkers would hash out potential solutions to those problems; in the afternoons and evenings, musicians from around the world would play the ancient and contemporary sacred musical styles of their countries, revealing not just the differences of expression among cultures, but more importantly, the similarities.

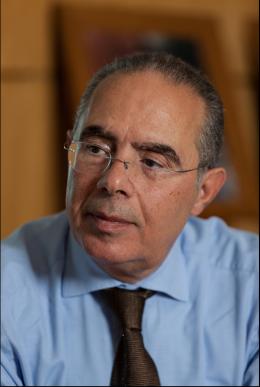

That mission has not changed. With the U.S. still at war in Iraq and Afghanistan and Muslims still painted with broad stereotypic brush strokes, it’s become even more important to bring people together for a little cultural nosh-and-tell, says the festival’s current president, former Casablanca governor Mohamed Kabbaj. I met with him one afternoon under the canopy of a huge oak tree in Fez’ Batha Museum courtyard. We had just watched a transcendent performance by the Tunisian singer and oud player Dhafer Youssef, whose group includes a piano player from Armenia, a bassist from Canada and a drummer from the U.S. “The cultures of humanity are not independent,” Kabbaj told me. “Every culture is built on a previous culture, and everyone has given something to this chain of civilization.” Some people, Kabbaj said, may not immediately see the links when communicating through translators, but when they hear the sound of a Middle Eastern oud next to that of a European lute or the kind of mandolin the late Bill Monroe played in his high-lonesome bluegrass hymns, they may begin to connect the dots.

The hope, Kabbaj said, is that festival attendees will take their epiphanies back home. “I think many people come to Fez and don’t know much about Muslim culture, and they discover there are many wonderful things. So they have this experience and they go back and create this experience elsewhere. If we have this in other cities around the world, we are helping people to understand each other. And that is good.”

One city that has taken cues from the Fez Festival is Los Angeles, which began its own World Festival of Sacred Music in 1999. Betto Arcos, my fellow Fez journalist and new travel companion, was on the ground floor of that event. During one of our many adventures into the maze of the Fez medina, over the crowing of roosters and chatter of French and Arabic voices, he told me how the L.A. event came about. It was initiated by the Dalai Lama, he said, “as a way to inspire people in all five continents to usher in the new millennium with a spiritual path.” That first year, Betto was an adviser on the eighty performances at venues all across L.A. With two subsequent festivals in 2002 and 2005, the event has now brought together a combined 200,000 people for some 6,000 performances by artists ranging from the Conjunto Folklorico de Cuba dance troupe to Pakastani qawwwali singer Rahat Fateh Ali Khan. “The director of the festival, Judy Mitosis, decided to continue organizing a festival every three years,” Betto told me. “The next one is in 2011.”

“Every culture is built on a previous culture, and everyone has given something to this chain of civilization.”

On a much smaller scale, a family of Fez veterans I met on another afternoon at the Batha takes the Fez Festival’s mission back to the American South each summer. For the third year in a row, fifty-four-year-old Diana Morningstar of Nashville, Tennessee, has accompanied her daughter, her Moroccan son-in-law and her half-Moroccan grandchildren to Fez. Back at home, Morningstar holds intimate versions of the festival in her house – small living-room concerts where local musicians ranging from Appalachian fiddlers to Latin jazz singers jam together and the attendees discuss pressing issues. Morningstar, whose long, snow-white hair makes her immediately recognizable at all of the Fez performances this year, sees a link between what she’s been doing in Tennessee and what Fez organizers have done here since the early nineties. When I identified myself to her as a fellow Southerner, her drawl became more pronounced and she joked with me in a faux-sassy swagger: “You know, Nashville is known as Music City U.S.A.?” she said, her velvety voice lifting slightly on the last syllable. “Well, I see Fez as kind of Music City W.O.R.L.D.”

Morningstar may have tapped into the essence of the Fez Festival’s mission, but the event is not without its controversy. Critics have suggested that by inviting secular artists like Ben Harper, organizers pander to larger audiences and water down the sacredness of the festival’s original intent. Music programming head Zineb Lemrabet defended that criticism on the Web site The View from Fez. “The spiritual essence is present in all types of music that we offer,” she said. “Even rock music has that essence, as does rap; for example, the song ‘Aissawa Style’” — a reference to a Sufi brotherhood founded in Meknes — “by Moroccan group H-Kayne.”

Others have complained that the festival’s North African presence – its musical soul – is eclipsed by the preponderance of artists from other parts of the world. “We question the reason for the severe lack of Maghreb artists within the activities of a festival that is originally from Morocco,” composer Aziz Hosni told The View from Fez. Kabbaj tersely countered that objection: “The program contains ninety percent Maghreb artists.”

When the festival started, in 1994, there were no concerts available to local Fez citizens who did not have tickets or could not afford them. That’s changed. In fact, most of the Moroccan and other regional North African acts appearing this year have performed at two venues open to the nonpaying public: the intimate Dar Tazi gardens, where Sufi musicians play nightly, and Boujloud Square, a vast open area where scents of cumin, coriander and grilled goat meat mingle with the sounds of children playing. That’s where the more populist-oriented performances attract thousands of families that sing along and dance together to the violins and fluttering rhythms of the bendir frame drums in the music of such regional artists as the fledgling pop singer Asmaa Jabri and Sufi superstar Abdellah Yaakoubi.

The festival’s more exclusive venues – the upscale Bab Makina and the more academic environs of the Batha Museum – host mostly internationally known acts like the Blind Boys, jazz men Murray and Shepp, and the Malian Afro-pop duo Amadou & Mariam. Such a wide spectrum of venues and musical styles, said Kabbaj, is the point of the festival: “The reason stems from wanting to make it more open to the cultures of different people and to not be dominated by a particular culture.”

AT DUSK on Saturday, the first full day of music, none of the ecstatic audience members who were pressed against the barrier separating the stage from the crowd at Bab Boujloud Square were complaining about musical styles or the ratio of Moroccan musicians to those of other cultures. The people in the largely local audience – some 5,000 strong – were too busy furiously waving bandanas around so fast they looked like the flapping wings of hovering hummingbirds.

Dressed in a long, flowing djellaba with brown stripes and a plain white kufi skull-cap, thirty-five-year-old Moroccan star Abdellah Yaakoubi – a member of the Issawi brotherhood of Sufis – had the crowd in a frenzy. A mass of young people in their teens and twenties – eyes ablaze, jumping up and down, fists pumping in the air – nearly fell over each other thrusting themselves toward the stage. But Yaakoubi barely moved. He just walked back and forth, singing snaky, curlicue-like melodies into his microphone as percussionists seated behind him pounded away. During the most intense climaxes of his songs, Yaakoubi’s voice sounded as though it was penetrating some invisible barrier between earth and heaven.

To many fans of Sufi music, that penetration is real. “Sufism is something transcendent, from the inside to the outer space where God’s mercy is. It’s coming from the soul, from the bottom of the heart,” said Marouane Hajji, a twenty-three-year-old Sufi-singing prodigy who performed another night at the nearby Dar Tazi. He was speaking in Arabic, through an intepreter. “People are in love and in touch with with the Sufis, because they know that this is the line between them and spirituality and flying into the space.”

Like gospel singers in the U.S., a Sufi singer’s sole reason for being is to reach God through music, says Blain Auer, a Western Michigan University professor of comparative religions who lives part-time in the Fez medina and the rest in Kalamazoo. Betto and I visited him one day for a walk to some of the medina’s more notable sites: the Moulay Idriss Mausoleum; the Attarine Madrasa, a Fourteenth Century Islamic school; the tomb of Ahmad Tijani, founder of the Tijani Sufi order. We ended the afternoon over tea and conversation on the rooftop of the Nejjarine Museum, a converted inn and warehouses where merchants in prior centuries would display their goods. “The idea (in Sufism) is that there are many ways to God and each individual needs to find his own unique way,” said Auer, a lanky, thirty-one-year-old academic whose pale skin, khakis and button-down shirt make him stand out in the medina like a Jack Russell terrier in a pack of Atlas shepherds. “For some people, music is a very powerful avenue, for some people it’s poetry, and for some people it’s prayer.”

“The idea (in Sufism) is that there are many ways to God and each individual needs to find his own unique way.”

The night before, at another Sufi performance, a scruffy-haired young singer had admitted to Betto that for him, music is a more important avenue than prayer. The statement probably wouldn’t go over well among fundamentalist Christians in the part of the South where I live. Auer said it wouldn’t go over well among some Muslims, either. “There are many Muslims who would say that this is not appropriate behavior, that there is no substitute for prayer and that prayer is an obligation,” he said. But Sufism is a very different kind of Islam from the fundamentalist branches most Americans read about or see on television and in movies. Like the Christian mysticism that inspired Catholic writer Thomas Merton, Sufism is the branch of Islam in which essential questions are raised: What does it mean to be a Muslim? What does it mean to be spiritual? What does it mean to be religious? “Sufism is the space where questions of tolerance in the religious tradition are raised,” said Auer. “Like, how much orthodoxy should we adhere to and where are the boundaries that we can stretch and expand upon?”

When I talked to Ricky McKinnie of the Blind Boys of Alabama on the afternoon of the group’s final-night performance, he sounded a lot like a Sufi. Dressed in a well-pressed sky-blue suit, McKinnie said he and his band keep coming back to Fez because they don’t see themselves as any more or less enlightened than any other person or culture seeking a spiritual connection. “See, communication is the main thing,” he told me. “We need to learn to sit down and to understand that your way doesn’t necessarily have to be the right way.”

MY MOROCCAN tour guide, Maurat, is laughing at me. We are driving past bountiful groves of cherry and apple trees, to the farm of one of his family members outside the village of Imouzzer-Kandar. I’m trying to ask him what his brother, whom we had just met outside an Imouzzer-Kandar cafe, does for a living. The only thing his friend Mohammed, the better English-speaker of the two, will tell me is that Maurat comes from a wealthy family. Maurat was trying to tell me something, too, but I have no idea what. And now he’s laughing. Betto, who knows just enough French to get himself in trouble, tries to help me out. “I think he’s saying ‘finance.’”

During our day-long excursion through the Moroccan countryside, Betto and I have played all kinds of communication games with our hosts. And we’ve shared our music. A panoply of songs has played through the tinny speakers of the car’s stereo system – everything from random radio songs by artists from my neck of the world (Dolly Parton and Louis Armstrong) to the Euro dance-pop of Italian diva Elisa to Maurat’s endlessly looping CD of Fez singer Said Sanhaji. Betto even brought along one his own CDs, which also got stuck on an endless loop: Ernesto Anaya’s Huapangueando, an eclectic compilation of traditional Mexican songs with modern arrangements released last year.

It is perhaps ironic that the pursuit of cultural empathy sometimes leads to cultural misunderstanding of comic proportions. Betto and I have been eager to hear Maurat and Mohammed play the traditional Moroccan music we’ve heard around Fez and to tell us what it means to them. But Mohammed, who has blended powdered hashish into his cigarettes and smoked the concoction throughout our trip, at one point turns to face Betto and me in back seat, his eyes red and wide grin revealing yellowing teeth: “I like Pink Floyd. I like Eric Clapton,” he says. “I like, um… Jim Morrison.”

Copyright Mark Kemp 2010

Below are more photos from my 2010 Moroccan journey; go here to see the full gallery of my photos from Fez. And for some extraordinary shots of the previous year’s Fez Festival, see Luann Williams’s photo galleries here and here.

Wonderful article and so well written. I will be leading a tour in Morocco of the Jewish history and culture in October/November 2022. My wife and I are both musicians (we play klezmer, Romani, Sephardic, etc.) and I would like to connect with some musicians in Fez. I want to put on a concert for the tour group where 3o minutes are the local Fez musicians and 30 minutes is myself and my wife jamming/playing with these artists. There are funds to pay these musicians. Can you send me any contacts/names of some musicians. I am interested in many genre of Moroccan music Sufi, Berber, Gnawa, so whatever genre they specialize in is fine with me. I look for ward to hearing from you. My website is not working well but I am all over google/Wikipedia, etc. I am a known writer, doc. filmmaker, musician, composer and photographer who has done a lot of research in Eastern Europe and the Balkans.