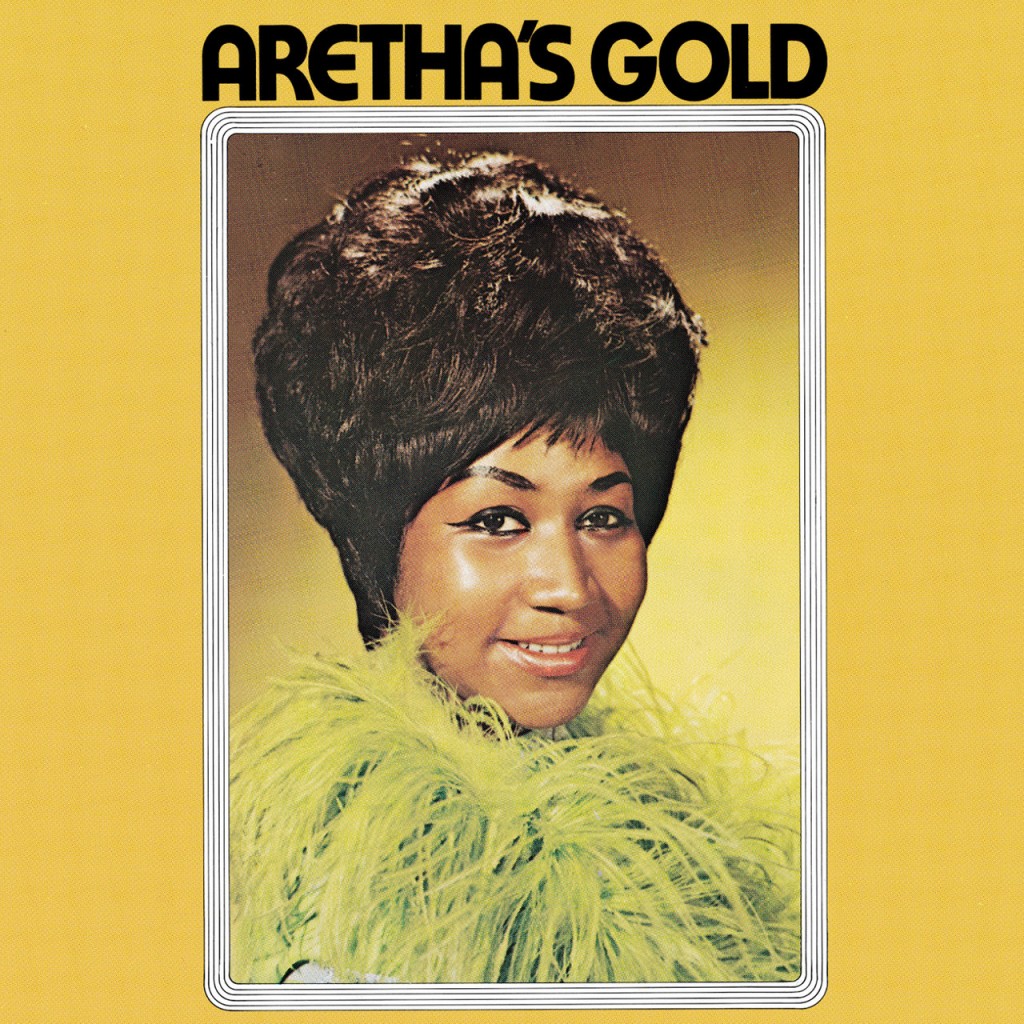

Childhood memory: I’m ten years old and sitting on the living room floor of my family’s North Carolina home in the early 1970s, vinyl albums and 45s scattered all around me — the Beatles, the Supremes, the Temptations, the Jackson 5. One record outshines all the others: Aretha Franklin’s 1969 greatest-hits collection Gold. On the cover she wears a gaudy feather boa, shiny black bouffant wig and tons of make-up. It has all the Top Forty pop hits that play on the local AM radio station in this small mill town: the funky, hard-hitting “Think,” the smooth, Southern-soul balladry of “Do Right Woman, Do Right Man,” the proudly female “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman.”

The song I like best, though, is different. It’s heady and whimsical, fueled by gritty gospel vocals but riding a sweet, soft-pop, Burt Bacharach/Hal David melody that flutters in the air like tissue: “I Say a Little Prayer” — three and a half minutes of musical bliss. “Forever and ever,” Aretha sings in call-and-response with her backup vocalists, “you’ll stay in my heart and I will love you.” And then, behind her husky purr, an angelic choir weeps: “To live without you would only mean heartbreak for me.”

NO ONE ON EARTH SANG a soul song as simply and effortlessly as Aretha Franklin, who died early today of advanced pancreatic cancer. Franklin was 76. She was the Queen of Soul, the embodiment of “diva,” a prodigious figure in the pantheon of American pop music of the past 60 years along with such other rock/R&B-era giants as James Brown, Elvis Presley, Bob Dylan and Michael Jackson.

Easily the most influential female African American singer that popular music has ever produced, Franklin took the gospel music of Mahalia Jackson out of church and onto the pop charts of the 1960s and 1970s. Between 1967 and 1973 alone, she scored 31 Billboard Top 40 hit singles, of which 14 reached the Top Ten, including “Respect,” “I Never Loved a Man (The Way I Love You),” “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman,” “Chain of Fools,” “Think,” “I Say a Little Prayer,” and “Spanish Harlem.” Over the course of her career, Franklin produced a total of 45 Top Forty hit singles, 20 of which reached No. 1. Her last Top Forty hit was her 1996 duet with Lauryn Hill on “A Rose is Still a Rose.”

Not even the youngest of today’s female singers of R&B-based music could claim she wasn’t hugely impacted by Franklin, says soul legend Bettye LaVette. “Look at American Idol — if a young girl wants to sound grown up and sophisticated, she’ll go out there and sing ‘Never Loved a Man,’” LaVette, Franklin’s peer and fellow Detroit-reared singer, said. “And if she wants to appear hot, she’ll go out there and sing ‘Respect.’ Aretha has been an inspiration to so many young singers. Her influence on women and on music in America — even the world — is huge.”

That’s just the beginning of Franklin’s importance to American music and culture. She also was an icon of the civil rights movement, her hits “Think” and “Respect” taking on a political edge in the years between the groundbreaking Civil Rights acts of 1964 and 1968. She sang at the funerals of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and gospel great Mahalia Jackson and at the inaugurations of presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. And Franklin, along with Otis Redding, who wrote her most famous hit “Respect,” was among the few Black-music stars to consciously cross the racial barriers that had begun to divide rock and soul by the late 1960s, performing for predominantly white hippies at venues like the Fillmore in San Francisco. In 1969 Franklin collaborated with the Allman Brothers Band’s iconic late guitarist, Duane Allman, on a stirring rendition of the Band’s “The Weight,” a song that turned the ears of younger generations of white Southern singers.

Shelby Lynne was 18 and living with her aunt and uncle in Monroeville, Alabama, when she first heard Aretha’s voice in the 1980s. “My world changed upon hearing the first down note,” said Lynne, who started out as a country singer but soon displayed deep soul influences. “Aretha was a singer’s singer, and since then she has ruled my world. She showed me fearlessness when singing, going all down to the gut for sounds, notes, qualities that mean so much in music. It’s not about notes as much as feel.”

IT WAS ALL ABOUT FEEL when Aretha Louise Franklin, who was born in a tiny clapboard house in Memphis, Tennessee, on March 25, 1942, began singing in the church where her father, the Rev. C.L. Franklin, preached. She was just 14 when she recorded her first album, a collection of gospel music, Songs of Faith, that included one of her enduring concert favorites, “Precious Lord (Take My Hand).” By then, the family was living in Detroit, where Aretha was a member of the New Bethel Baptist Church choir. Even at her young age and on those songs — particularly the rousing “He Will Wash You White as Snow” and smoldering “Yield Not to Temptation” — Franklin’s voice and delivery had the controlled fierceness and earthy lilt she would put to her later secular hits like “Think” and “Natural Woman.” Under the tutelage of a young and equally fiery gospel belter, the Rev. James Cleveland, Franklin’s early church performances created a buzz among the pop-music cognoscenti, and within four years she was getting offers from mainstream secular labels.

At 18, Franklin signed with Columbia and set out for New York, where she worked with John Hammond, the famed talent scout who had brought Billie Holiday to the public eye. Hoping Franklin would be Columbia’s next Holiday, Hammond teamed the young singer with pianist Ray Bryant’s jazz orchestra for her 1961 debut, encouraging Franklin to temper her gritty gospel edge and sing more in the pop-jazz style of one of her idols, Dinah Washington. Franklin’s second Columbia album, though still jazz-based, crossed over to the pop charts on the strength of the twangy “Rock-a-Bye Your Baby with a Dixie Melody,” which prominently featured her signature gospel scream. But Columbia was never able to really draw out Franklin’s Southern soul. Although she would record another six albums for the label over the next five years — some including performances that would shame most singers — it wasn’t until Jerry Wexler of Atlantic Records stepped in that she became the Aretha Franklin who would define ’60s and ’70s soul music.

Wexler knew some players down in tiny Florence, Alabama — not far from Aretha’s roots — who along with the musicians at Memphis’ Stax Studios were making some of the grittiest soul and R&B in the country. He signed Franklin to Atlantic and in 1966 sent the singer packing for her legendary sessions at FAME Studios with the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section. That group included players who had backed other R&B singers like Wilson Pickett and Percy Sledge — notably, rhythm guitarist Jimmy Johnson, who had a funky, scratchy signature style; bassist David Hood (father of the Drive-By Truckers’ Patterson Hood), whose raw, steady-rolling gait had driven Clarence Carter’s “Too Weak to Fight” the year before; and Spooner Oldham, whose deep, swampy, church-like keyboards would lift Franklin’s voice much like the piano and organ had at her father’s Baptist church.

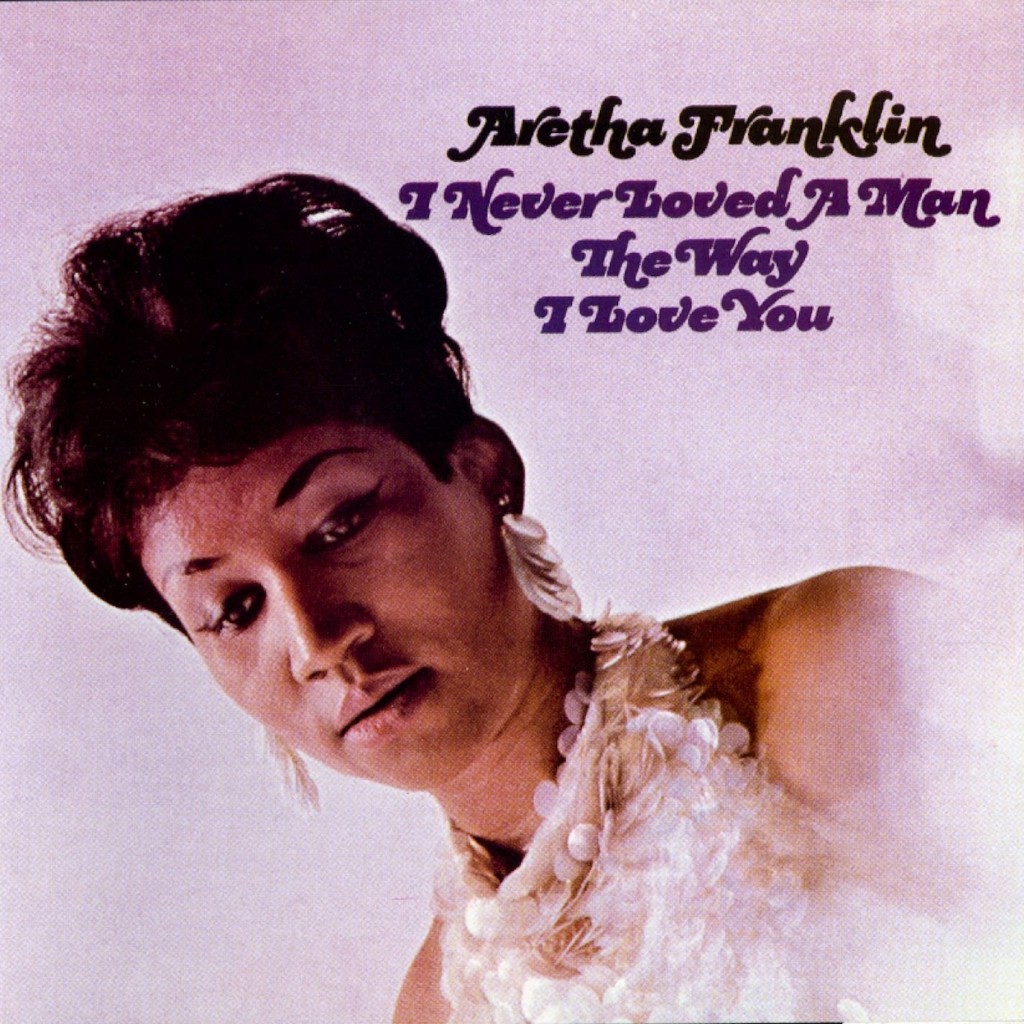

Franklin only recorded two songs at FAME — her breakthrough hit “I Never Loved a Man (The Way I Love You)” and part of “Do Right Woman, Do Right Man.” During the sessions, one of the horn players reportedly came on to Franklin, angering her then-husband Ted White. A fight ensued, and Wexler flew the core Muscle Shoals crew to New York to finish the recording of her Atlantic debut, I Never Loved a Man the Way I Love You. It was Franklin’s long-overdue blockbuster, shooting to #2 on the strength of the #9 title song and chart-topping “Respect.” The LP remains one of the most well-loved and well-respected albums in the history of soul and R&B; its sound not only would forever define Franklin’s career but it would inform much of ’70s rock & roll, from the Rolling Stones’ swamp-rock moves on Sticky Fingers to hits like Rod Stewart’s “The First Cut is the Deepest” and Bob Seger’s “Mainstreet.”

Franklin was at her creative and artistic peak during the late ’60s and early ’70s, releasing one powerful set of songs after another: Lady Soul and Aretha Now (which shot to #2 and #5, respectively, in 1968), Soul ’69 (#15, 1969), and the sorely under-appreciated Spirit in the Dark (#25, 1970), which found her back with the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section, as well as with Memphis keyboard player Jim Dickinson’s Dixie Flyers and guitarist Duane Allman, and for which she wrote almost half the songs. Those were followed by the phenomenally influential Young, Gifted and Black (#11, 1971), the fierce Aretha Live at the Fillmore West (#7, 1971), and the transcendent Amazing Grace (#7, 1972).

By the mid-’70s every female R&B singer in the world wanted to sound like Aretha Franklin, from peers such as Roberta Flack to fledgling funk and soul belters like Chaka Khan. With the emergence of disco by the late ’70s, however, Franklin’s gritty Southern soul fell out of favor among urbane club kids, although her collaboration with Curtis Mayfield on the 1976 soundtrack to Sparkle was a high point, reaching #18 and producing the sizzling #17 hit “Hooked on Your Love.” In the ’80s Franklin moved from Atlantic to Clive Davis’ new Arista Records, where she made some respectable albums — 1985’s Who’s Zoomin’ Who? (#16) produced the #3 hit “Freeway of Love” — but none reached the creative heights of her early-’70s prime. That album’s follow-up, 1986’s Aretha, also charted surprisingly well, mainly on the strength of her first #1 pop hit since “Respect” — a flaccid duet with George Michael on “I Knew You Were Waiting (For Me).”

Adult memory: I’m 38 years old, the vice president of music editorial at VH1, and I’m sitting in a conference room with several fellow executives discussing the 1998 Diva’s Live concert. Conversation turns to Aretha Franklin — how to get her from Detroit to New York City by bus, as she has long refused to travel by air. My mind wanders back to the family living room floor of my early-’70s childhood, listening blissfully to “I Say a Little Prayer.” Later, I’m amused by the little power struggles among Aretha and the other divas — Mariah Carey, Celine Dion, Gloria Estefan, Shania Twain — who will share the stage with the Queen of Soul at the show; none, in my mind, deserve to share the same room with Aretha.

Fast-forward to 2002. I’m in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, doing research for my book Dixie Lullaby: A Story of Music, Race, and New Beginnings in a New South. I’m talking with Jimmy Johnson, who played guitar on Aretha’s I Never Loved a Man the Way I Love You. Her voice on “Do Right Woman, Do Right Man” drifts from the sound system in Johnson’s studio and he appears to be in a trance as he listens to himself play alongside Aretha’s ethereal voice. At one point, Johnson whispers — to himself, kind of, but also to anyone who has ever heard Aretha Franklin perform — “We gave our hearts and souls to those singers.”

BY THE LATE ’90s Aretha Franklin was living R&B royalty. Though her recordings during this period were spotty, her performances remained stellar. She scored her last major hit when Sean “Puffy” Combs teamed her with Lauryn Hill on 1998’s A Rose is Still a Rose, which reached #30 (#7 on the R&B chart) on the strength of its #26 title song. But her best recent work came when she teamed with Mary J. Blige, her most obvious latter-day successor, for “Never Gonna Break My Faith,” a track on the 2006 film soundtrack Bobby, Emilio Estevez’s biopic about the fallen Sen. Kennedy of Franklin’s ’60s prime.

In 2008 Rolling Stone named Franklin the #1 best singer of the rock era; the following year she was the obvious choice to sing “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee” for the inauguration of America’s first Black president, Barack Obama. In May 2010, Yale University presented her with an Honorary Doctorate in Music. Later that year, it was reported that Franklin was battling pancreatic cancer, but she later denied it. By 2015 Franklin had bounced back and was able to perform a rousing version of “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman” for President Obama, his family and a packed Lincoln Center in Washington, D.C. But Franklin’s health took a turn for the worse in more recent years and she announced last year that she would be retiring from performing after the release of her 2017 album A Brand New Me.

Then, in the morning hours of of Aug. 13, members of Franklin’s family reported to Detroit news anchor Evron Cassimy of WVID that the singer was gravely ill in the hospital, and they asked fans to pray for her. This time, the Queen of Soul wouldn’t pull through. Shortly after it was announced that Franklin had died, Thom Jurek, a fellow music journalist based in the Motor City, wrote on my Instagram page, “We here in Detroit have no idea what our city looks like without Aretha.”

______________________________________________________________________________________

WATCH THE QUEEN OF SOUL THRILL A GREAT AMERICAN SONGWRITER AND BRING TEARS TO A PRESIDENT’S EYES: