In late 2016, I was invited out to David Crosby’s home in Santa Ynez Valley, California. I was an editor at Acoustic Guitar magazine at the time, and Crosby wanted to show me his guitar collection. He darted around his bedroom like a kid on Christmas morning, showing me this guitar and that one — the one that he played at Woodstock, the one that he prefers to play today. He was proud of his guitar collection, and he wanted us (and guitar aficionados everywhere) to know about these prized gems. But he didn’t shy away from talking about his troubled past: his drug years, arrests, squabbles with fellow members of The Byrds and Crosby. Stills, Nash and Young. Crosby is nothing if not honest. He’s also a bit of a crank. And all of that came through in our fascination conversation, in which he also played me some of the most iconic guitar riffs in rock history, which you can see in the video at the end. It was a “stunning” California afternoon, as Crosby would put it.

The troubled CSNY singer’s story as seen through the prism of his guitars

By Mark Kemp, Acoustic Guitar, January, 2017

“IT’S HOPELESS,” David Crosby says. “If you ask me about dates and stuff, it’s not going to work.” Crosby’s annoyed. Specificity is not his thing. “I’m one hundred and ninety two years old,” he continues. “I can’t remember which year what happened.”

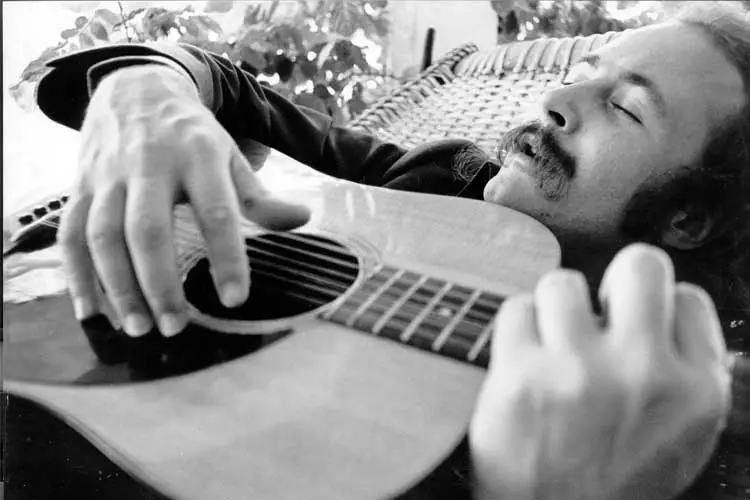

Crosby, who’s actually 75, is sitting in an upright chair next to an earthy stone fireplace in the sunroom of his sprawling home in California’s Santa Ynez Valley, talking about some of his most prized acoustic guitars. There’s the Martin D-18 that he purchased in Chicago for $300 when he was barely out of his teens and playing the folk coffeehouses of the early 1960s. That’s the guitar Crosby converted into one of the most iconic 12-string mods in rock — around the time he joined the Byrds in 1964, and then took to the world stage five years later when Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young debuted at Woodstock. There’s also the ragged D-45s that Crosby bought new in Berkeley in 1969 and still plays at his concerts. And then there’s the sterling blonde custom McAlister that he’s been known to kiss onstage after particularly fiery performances.

But the guitar Crosby is thinking about right now is the one that got away. He becomes wistful remembering the 1939 Herringbone that he traded for “substances” during his years in the grips of a $1,000-a-day cocaine and heroin addiction. “It’s not a pleasant memory,” Crosby says in a near whisper, his eyes misting slightly at the sides. “It’s just one of those things I gotta live with. I’ll regret it for the rest of my life. But there it is — I did it. That’s how it was.”

HOW IT IS TODAY for Crosby — dressed casually in a knitted beanie, red T-shirt, jeans, and suspenders, his signature handlebar mustache now white as a Salvation Army Santa’s — is very different from how it was. In the three decades since 1983, when he sobered up in a Texas prison while serving nine months for drugs and weapons convictions, Crosby’s received a life-saving liver transplant and written far more songs than he ever did in his ’60s and ’70s heyday. He’s released five solo albums including his latest, the solo-acoustic Lighthouse, that finds the folk-rock icon going back to his folksy roots, and the forthcoming Sky Trails; four with CSN or CSNY; two with CPR (featuring Crosby, Jeff Pevar on guitar, and Crosby’s son James Raymond on keyboards); and several live recordings in each of those configurations. He’s currently on an extended solo-acoustic tour, mixing early CSN classics such as “Guinnevere” and “Déjà Vu” with more recent material.

To casual fans, Crosby is the main character in the longest-running, non-televised celebrity reality show, regularly reuniting and breaking up with CSNY (and its various offshoots), most recently calling it quits yet again after a public feud with his one-time main advocate in the group, Graham Nash. “There’s a lot of personal stuff going on between me and Crosby,” Nash told Acoustic Guitar in 2016. “CSN and CSNY is over. That’s the way it is.”

For now, anyway.

Meanwhile, Crosby’s kept the gossip columnists in business for reasons that have little to do with music. In 1998, his reunion with son Raymond, whom Crosby had given up for adoption 36 years earlier, was a hot topic topped only by his announcement two years later that he’d sired two children for then-celebrity-couple Melissa Etheridge and Julie Cypher. Crosby also hasn’t avoided legal troubles altogether. In 2004 he was arrested yet again on guns and drug charges, but the drug charge (for a small amount of marijuana) was dismissed and Crosby only had to pay a $5,000 fine for the weapons offense.

Through it all, Crosby’s passion for acoustic guitars has only deepened. He’s a collector whose repeated use of words like “stunner” and “beauty” to describe his guitars, their sound, and their playability is a testament to his genuine love affair with the instruments. “I’m appropriate for you guys,” Crosby says, referring to Acoustic Guitar magazine, as he shows off the 15 guitars he’s painstakingly cherry-picked and set up in his bedroom for us to showcase. He reaches for each instrument, one at a time, strums it, and reels off the specs like a kid describing the treasures of a particularly bountiful Christmas morning. “I’m an acoustic guitar fanatic!”

CROSBY, THE YOUNGER SON of Hollywood cinematographer Floyd Crosby (Tabu, High Noon, The Pit and the Pendulum) was born August 14, 1941, and was about 14 when his brother Ethan gave him his first guitar, a Silvertone acoustic. “He got a new one, so he gave me his old one,” Crosby remembers. “I learned two chords and I played them endlessly.” He and Ethan, who also played stand-up bass in jazz and Latin combos, began performing together as a folk duo. “As soon as I started playing live, that was it—I was done,” Crosby says.

By the time Crosby hit his 20s, he wanted a great guitar—he’d had a Vega 12-string, but Martins were calling his name. “I was in Chicago working [the folk clubs] Mother Blues and Old Town North, and I took the money I made and I found a D-18 in a shop way out in the suburbs,” he remembers. “I rode out there on the bus, bought it, and brought it back. It was a really good, ’50s, lightweight D-18.” He points to his bed, where he’s neatly lined up seven of the 15 guitars: “It’s what became that 12-string over there.”

The conversion of his D-18 into a 12-string happened when Crosby got back to California and visited Lundberg’s Fretted Instruments, a shop in Berkeley that sold and repaired vintage acoustics. “I went to [Jon] Lundberg and said, ‘Listen, I want this to be a 12-string. Can you make this into a 12-string?’ He said, ‘Yeah,’” Crosby remembers. “They made it into a 12-fret 12-string, which turns out to be part of its success story.”

According to Crosby, the repairman at Lundberg’s had to push the bridge to the center of the top to make it a 12-fret. “So the bridge is in a different place than it is on a 14-fret,” Crosby explains. “That’s one of the reasons this thing sounds as good as it does. The other reason is that it has a spectacular top on it.” He walks over to the bed, picks up the instrument, and begins tuning it. “An amazing guitar,” he exclaims as he sounds the two low E strings. They ring out clearly and with surprisingly thick volume. “And that’s just two out of 12. It’s loud!” Crosby says with a cocky wink. “Near as I can tell, it’s still the best 12-string I ever encountered anywhere, and I have played some stunner 12-strings.” He points to the guitar’s battle scars. “It’s kind of beat up now. It’s been with me a long, long time.”

In 2009, Martin issued a commercial version, the D-12 David Crosby, built from the specs of his converted D-18. The D-12 has a D-14 body style, mahogany back and sides, a spruce top, and Crosby’s signature between the 16th and 17th frets. “It’s a cool guitar, too,” he says, again pointing to the collection. “I have one of the prototypes right there.”

CROSBY’S 12-STRING MOD was the only guitar he owned in 1964, when he ambled into one of his Los Angeles mainstays, the fabled Troubadour club on Santa Monica Boulevard, and sang some harmonies with fellow folkies Jim McGuinn, who later changed his name to Roger, and Gene Clark. Crosby had seen McGuinn when the guitarist accompanied ’50s-era folk group the Limelighters. But Clark, fresh from the New Christy Minstrels, was a new kid on the block.

“Roger and Gene were up there singing these songs that Gene had been writing after he saw the Beatles,” Crosby remembers. “He was fascinated with the Beatles. He wanted to be the Beatles—as we all did—but he didn’t know the rules about music. He was completely uneducated, like me, so he just did what felt good.”

McGuinn, on the other hand, was an accomplished guitarist, having played not only with the Limelighters, but also the Chad Mitchell Trio, Judy Collins, and even Bobby Darin. “So he and Gene are sitting there playing and I just sit down with them and start singing harmony,” Crosby says. “They both go. . .” Crosby makes a facial expression of awe and silently mouths the word, “Wow.”

The experience reminded Crosby of his first job as a busboy at a coffeehouse in his hometown of Santa Barbara, where he worked for free just for the opportunity to sing harmonies with the paid folksinger. “The only reason I got through high school was the choir,” he says. “Every once in a while we’d get all in tune, and the whole rest of the room would lift up and get magical for a minute. I love that shit! It feels real good.”

As soon as Crosby says this, a wind chime outside on the patio rings behind him like punctuation.

Shortly after their Troubadour meeting, Crosby, McGuinn, and Clark, along with drummer Michael Clarke and bassist Chris Hillman formed the Byrds, and began mixing their acoustic folk sensibilities with the electric pop appeal of the Beatles. McGuinn’s signature Rickenbacker 12-string jangle gave the Byrds an instantly recognizable sound, and the group immediately shot to the top of the pop charts in 1965 with sparkling covers of Bob Dylan’s “Mr. Tambourine Man” and Pete Seeger’s “Turn, Turn, Turn.”

“I’d started out in the Byrds with my 12-string, because it was the only guitar I had at the time,” Crosby says. “But that didn’t really cut it for being in the Byrds. I needed—I thought—what George [Harrison] was playing: a Gretsch. So I got a Tennessean, and pretty soon after, a Country Gentleman. That was my main electric guitar for a long time. It was a very good electric guitar. I had a lot of fun with it. I put an STP sticker on it.”

Other Top 40 hits followed for the Byrds, including “Eight Miles High,” “Mr. Spaceman,” and “So You Want to Be a Rock ’n’ Roll Star,” but after three years Crosby was getting restless. He’d written a musically adventurous song, “Triad,” with racy lyrics about a three-way orgy, for the group’s 1968 album The Notorious Byrd Brothers. The Byrds nixed it, but Jefferson Airplane recorded an acoustic version for their Crown of Creation record of the same year.

“We were changing very drastically and very fast,” Crosby says of the Byrds. “I was learning how to write and I wanted to write—I wanted more, I wanted a bigger piece of the pie. So I said I wanted to write some of the songs we were recording and, um . . . I don’t think I was a very nice guy at that point. I was pretty. . .”—he pauses for a good 15 seconds, gazing blankly out the back window at the rolling hills of his property—“volatile. There’s a good word. In any case, we had disagreements and they asked me to leave the group, so I did.”

BY THE TIME CROSBY left the Byrds, he’d been hanging out among a growing group of musicians who’d moved to the Laurel Canyon area of Los Angeles, including Joni Mitchell, a few of Crosby’s fellow Byrds, and members of Buffalo Springfield, including guitarists Neil Young and Stephen Stills. “I was working at writing songs but not really knowing what direction to go in, and I was hanging out with Stephen Stills because Stephen’s group had fallen apart,” Crosby remembers. “I had already sung with them at Monterey Pop [Festival], because Neil had split on them.”

Crosby rolls his eyes.

“That’s Neil.”

It wasn’t just Stills’ soulful harmony vocals, but also his dazzling acoustic-guitar work that impressed Crosby. “He got stuff out of an acoustic that people just didn’t get out of them—a lot of attitude, a lot of punch,” Crosby says. “So we would hang out together—he and I and [Jimi] Hendrix, he and I and Cass [Elliott], he and I and eventually Nash.”

Crosby and Stills found their sweet spot with Nash, and CSN was born. “It was so easy,” Crosby says. “We didn’t even think twice about it. When we heard ourselves sing together, the three of us, we knew that we wanted to do this.”

Initially, all three members were playing only acoustic guitars, and Crosby wanted them all to be the same. “Martins. All of us,” he says. “I had a couple of D-28s that I don’t think I have anymore, but then in 1969, Martin started making D-45s again. They hadn’t done that since before the war, and soon as I saw one, I wanted it. So I went again to Lundberg’s, and they had a number of them. I picked the three best and bought them. Right then. Still got ’em.”

It wasn’t long after CSN released its self-titled debut album in 1969, followed the next year by Déjà Vu, with Young in the mix, that things began falling apart. And that’s been the nature of the relationship for almost a half-century since. Perhaps surprisingly, Crosby says the four were never good co-songwriters, just great singers. Unlike his current songwriting partnership with son James—as well as past partnerships such as the one he had with the Airplane’s Paul Kantner, with whom Crosby and Stills wrote “Wooden Ships”—Crosby says there was never much chemistry among the members of CSN or CSNY.

And yet, even as adamant as Nash was in the 2016 AG feature, he’s since backpedaled on his pronouncement that CSN is over for good. “You never know,” Nash later told Ultimateclassicrock.com. “If Crosby came and played me four songs that knocked me on my ass, what the f— am I supposed to do as a musician, no matter how pissed we are at each other?”

And so continues the saga of rock’s longest-running soap opera.

Acoustic Guitar, 2017

Watch excerpts from the interview