It was a tough week for my tinnitus. Back in Los Angeles a couple of nights earlier, I’d experienced the loudest concert I’d ever been to — and I couldn’t get enough. So I hopped on a plane to Houston, Texas, where My Bloody Valentine would recreate the experience for me once again, this time in the vastness of America’s geographically largest state. I was following the Irish band — the preeminent experimental dream-pop act of the early 1990s, who’d just released their masterpiece, Loveless — from gig to gig. I wanted to learn more about what made this spectacular band tick, and then write about it for Option, the experimental music magazine that I edited at the time. As the plane descended into Houston, I saw a quote in an inflight magazine article about Texas. That’s where this story begins.

Into the Belly…

By Mark Kemp, Option, May 1992

WELCOME TO “GOD’S OWN COUNTRY,” as a Texas politician recently decribed his home on the range, “where the grass grows tall and the wind blows free and anyone who says ‘income tax’ gets their mouth washed out with soap.”

“Have you ever been to El Paso?” Ann Marie Shields asks, her voice full of concern. She’s the sister of My Bloody Valentine guitarist and singer Kevin Shields, and the group’s tour manager. “We drove through it yesterday,” she continues. “It’s this big city that’s completely poor, just totally devastated.” Bilinda Butcher, the group’s other guitarist and singer, is wedged between the Shields siblings, providing echoes. “Really poor,” she says.

“I’d never seen such a place in my life,” Ann Marie continues. “It was just unbelievable — all those tiny, run-down shacks.”

“Unbelievable,” Butcher softly repeats.

It’s a Friday, around supper time, and the members of My Bloody Valentine are squashed together in a rental van and barreling down one of the many endless, flat streets of Houston, Texas. They’re headed to sound check at the Vatican, a cavernous, cinderblock dive located at the corner of Washington Avenue and Cohn Street in the central part of town.

Houston is the fourth-largest city in the United States, and a hotbed of violent crime. Last year, 671 people were murdered here, sometimes for nothing more threatening than an awkward glance. Residents are so frightened they’ve caused stock in handguns and home security systems to soar; in fact, folks saying “income tax” in Houston today are as likely to get their mouths washed out with a .38.

Amid this eerie, violent Southwestern Americana, the Valentines will do a 45-minute set of otherworldly music tonight before a sold-out house on a package show with Dinosaur Jr. and Babes In Toyland. Two nights earlier, the Valentines stirred up so much energy at the Roxy in Los Angeles that kids were stagediving and slamdancing. That wouldn’t be so odd except that My Bloody Valentine’s sound is hardly music to mosh by.

Kevin Shields, Bilinda Butcher, Debbie Googe and Colm Ó Cíosóig.

Kevin Shields, Bilinda Butcher, Debbie Googe and Colm Ó Cíosóig.EARLIER IN THE DAY, Kevin Shields sits at a poolside table at the group’s hotel, a glass of iced tea beside him and 70 degrees of Texas sunshine all around. He’s describing what it feels like to lasso a lifetime’s worth of tension and fling it out to hundreds of people in a melange of beautiful melodies and disturbing dissonance. Some folks, he says, just get out of hand.

“I’m not afraid of anyone coming up onstage and personally hurting me, because I’m big enough to take care of myself.” Shields says, glancing off into the pale blue afternoon. “It’s weapons I worry about.

“There’s always a few people who really, really resent it,” he says of his band’s music. “Some people get really aggressive, angry, mad. They feel like we’re a bunch of wankers who have no right to do this. They take it personally, as a massive insult. Sometimes I think, shit, anything could happen.”

At the moment, he’s thinking about the gig in L.A. “I saw this big skinhead guy moving his way aggressively through the crowd,” says Shields, who speaks and sings with an almost self-effacing gentleness, but makes his guitar yowl like a wounded beast. “I looked at one of the guys in the band and said, ‘Watch it, there’s someone coming towards us!’ But then he stopped about halfway through and stood there and stared. You just never know.”

What sets off such intense reactions is a song called “You Made Me Realise,” the emotional and psychological breaking point of every My Bloody Valentine show. For about an hour, the group coils through a set of noisy, ambiguous songs, like “I Only Said,” “Soon” and “To Here Knows When,” all marked by simple, delicate melodies and hushed male/female vocals, and wrapped up in wavering layers of textured guitar and drums. The result is a sustained roar of glorious experimental rock, with tiny pop sounds occasionally peeking in and out, above and beneath the haze. A barrage of photographic images, circles, and flickering lights are projected onto a backdrop, adding visual punch to the musical chaos.

And then comes the onslaught of “You Made Me Realise,” which, depending on the night and the mood of the band, can be up to 20 minutes and at least 100 decibels of pure, unrelenting, confrontational white noise, exacerbated by blinding strobe lights.

“It seems like such an odd thing to do, you know, to make a lot of noise,” Shields admits. “But I think we take it way past the point of acceptedness. It takes on a meaning in itself. I don’t know exactly what it means, but it basically transcends stupidity. For us it’s genuinely…” He trails off, glancing again into the hazy Lone Star sky. “It’s the most relaxing moment of the whole gig.”

I HAD FOLLOWED the Valentines to God’s Own Country because they stood me up in the City of Angels. It wasn’t out of meanness; apparently, a tire on their equipment trailer had blown out on the way from San Francisco to Los Angeles, and the weight of the equipment had damaged the rims, delaying their arrival. The group spent the entire next day in L.A. searching for a replacement truck that was so weighted down during the trip to Houston that it puttered all the way across the desert at less than 55. “It’s been horrible,” Kevin says. “But the good thing about it was that we were driving in the daylight and I got to see Arizona and New Mexico. I’d never been in the desert before.”

In the last two years the Valentines haven’t seen much daylight at all. They’ve spent their time holed up in various London studios in the middle of the night recording their latest album, Loveless. It took so long to record that, Shields says, “Everybody had completely lost faith in us.” To be sure, the British music press was having a field day trying to predict what it would sound like. When the EP Tremolo came out as a teaser, some felt the band had lost its edge. “We weren’t trying to make the perfect album or anything,” Shields says defensively, in response to an article that suggested the group had been trying to do just that. “The reason it took so long was because we had started out on the wrong foot and never got back on the right one. Right up to the last minute, we kept thinking we would be finished in a couple of months — two years of thinking we would be finished in a couple more months.”

Like the group’s live shows, Loveless flits back and forth between light, whimsical pop melodies and deep blotches of noise and wavering dissonance. The vocals are set way back in the mix — further back than ever before — and function more as added instrumentation than as verbal communication. Not to say the Valentines don’t communicate feelings in their music; it’s just that the feelings aren’t especially tangible ones. Still, when Butcher hisses, “Midnight wish/Blow me a kiss/Hoping I’ll see you,” in the song “Blown a Kiss,” you can feel the longing, even as her voice snakes in and out of the drone. It’s just not the sort of longing that can be summed up in a “Dear Abby” column.

“It’s not like we’re thinking, ‘Oh, I feel really bad or angry and I want to make something that will represent that,'” Shields says of the group’s songwriting process. “It’s done more in a really unfocused sort of way. The only time it makes sense is when it all comes together. When I write lyrics, I take liberties with them because I’m not particularly trying to convey anything to anyone in words. It makes sense to me and gives me enough conviction to sing the songs, but it doesn’t necessarily make a lot of sense to other people.

“That’s what all our music is like,” he continues. “It’s ambiguous, but in an ethereal, flowy way. It’s kind of see-through. And the lyrics are only as substantial as the impression you get from the entire song.”

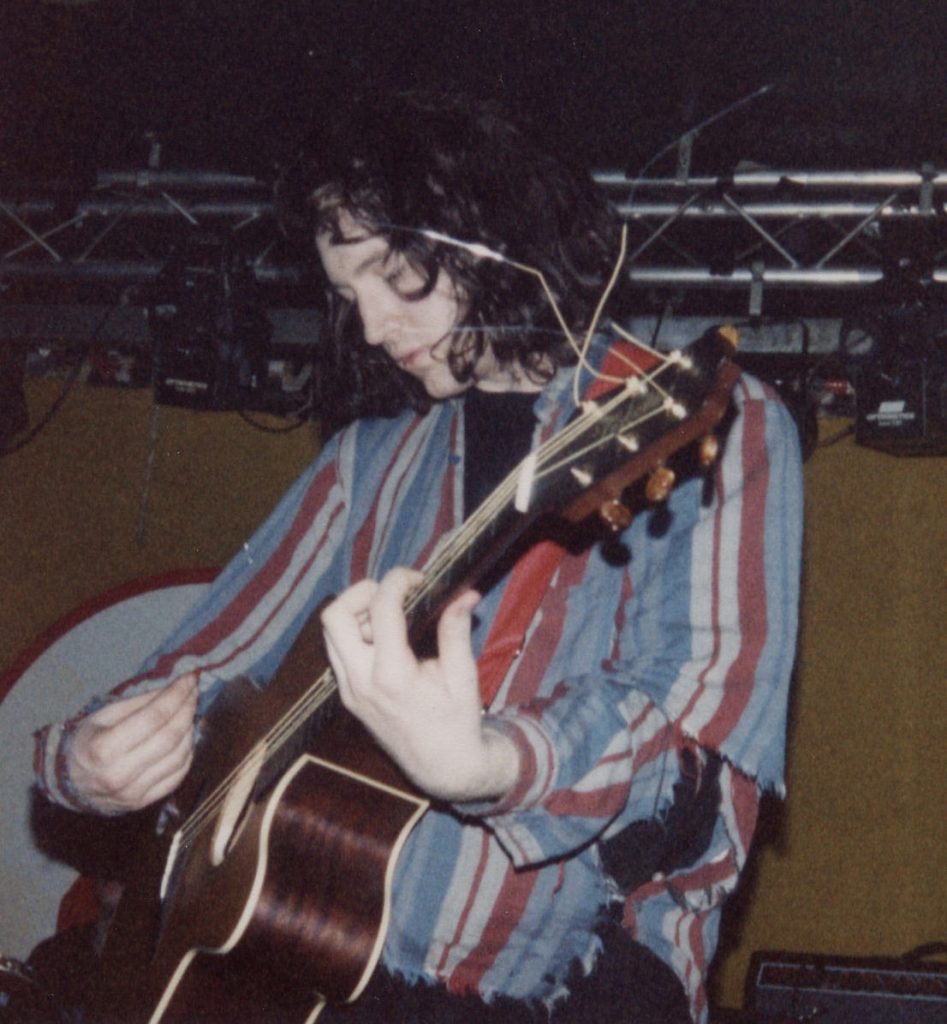

Kevin Shields in 1989. (Photo by Graham Racher)

Kevin Shields in 1989. (Photo by Graham Racher)KEVIN SHIELDS is the quiet, sensitive type, almost to a fault. He has longish brown hair, and calm, gentle features that are enhanced by a pair of wire-rimmed glasses he wears when he’s not onstage. With his prominent nose, small lips, and an ever-so-slight overbite, Shields looks a bit like John Lennon — only prettier.

Born on New York’s Long Island, he was uprooted at ten and moved to Dublin, Ireland, forced to leave a cozy American childhood behind and acclimate himself to a new, completely alien culture. “I remember very vividly the day we moved,” he says. “When something that traumatic happens, you remember every detail. I’d left everything behind me — not just my friends, but everything I was into as a kid. I had been really, really into things like Godzilla films and Saturday morning cartoons. Ireland had none of that; it was 20 years behind America back then.”

It took time for Shields to get over his identifcation in the neighborhood as the American kid on the block, but he managed. For one thing, Ireland had English TV, which carried the popular music show Top of the Pops. “At that time it was suddenly completely blown over by glam rock,” he says. “I hadn’t come across that in America. When I was in America the only rock bands kids were into were, like, Three Dog Night, bands like that. In England, even little kids were totally into glam rock, like T-Rex and even Roxy Music. Because it was glam rock. It was pop music. It was on Saturday morning TV. It was like cartoons. All the kids in my neighborhood were into, like, Slade.”

By the time he reached his mid-teens, Shields had befriended Colm O’Ciosoig, a shy, wiry kid a couple of years younger than himself who played drums. The two both shared an interest in punk rock and in thinking of themselves as rebellious. So like any other normal teenage misfits, they formed a band. “We had a lot of different bands together,” says O’Ciosiog (pronounced o-COO-sak), “a punk band, a poppy kind of band. But then we just started experimenting and turned out this total dirge music. Once we went out to this shopping mall and plugged into an outside plug and made a lot of noise on a Sunday afternoon. We thought it was pretty rebellious. It was actually quite funny. We ran away before anything happened, though.”

In 1984, Shields and O’Ciosoig formed My Bloody Valentine, which was named for a B-grade Canadian slice-and-dice flick. Though the music on the group’s first EPs (variously on the Tycoon, Fever, Kaleidoscope Sound and Lazy labels) was much different from what the Valentines would become known for, their experimentation on those early releases contained the seeds of what showed up later on their Creation EPs, their debut full-length, Isn’t Anything, and the new Loveless.

The impression you get listening to My Bloody Valentine is of a group of ghosts inside a monstrously big machine, trying to sing and play their way out of it. But it’s really not so spooky. In fact, Shields and Butcher are so normal they have a family life away from the band, raising an eight-year-old child, Toby, from Butcher’s former marriage.

“He’s a good kid,” says Shields. “When we’re out on the road or recording, he goes to this really great boarding school called Summerhill. It’s so radically different from other schools that the kids are seen as kind of like a tribe, like a society of children. They actually have a vote on everything. They don’t have to do anything, but they vote, so there are rules. But they’re amusing rules because they come from a kid`’s point of view. Like, they can curse, but you can’t call anybody a cucumber because the children don’t want you to.”

A SCREAMING COMES ACROSS the club. Shields and O’Ciosoig are standing onstage at the Vatican, working out the glitches in the sound system. On the walls surrounding them are graffiti from other bands: there’s the Pixies logo in light blue, Nirvana in hot pink, and Primus in gaudy orange. Off in one corner, Kat Bjelland of Babes In Toyland holds a casual conference with her band, and in the mid-section of the club a cluster of Dinosaur Jr. roadies kicks a hackeysack around. Shields steps down to fiddle with an effects box while snippets of songs from Loveless blast out of the speaker columns along with shrill feedback.

Bassist Debbie Googe, meanwhile, is standing with Bilinda Butcher at the front of the club, as far away from the noise as possible, talking about Butcher’s first gig with the Valentines. “She had to hold Toby the whole time,” Googe says, laughing. “He wouldn’t let her go. When it came time for us to go onstage, he just wouldn’t let go.”

Butcher, whose long brown hair is tucked casually behind her small ears, giggles. She’s the quiet, sensitive type, too. (It seems to be a requirement for membership in the band; in fact, all of the Valentines are so quiet and shy it’s as if they’re vying with each other to be the least noticed.) Butcher’s arms are folded; a silly grin on her face accentuates her red jeans and gold, glitter-speckled red sneakers. “Toby was just three then,” she says. “He was fine until I got on the stage and then he was like, Whaaaa. So I had to stand there and hold him. For about an hour.”

The stress of being in a relationship with the leader of the band is something Butcher doesn’t think about all that much, though it is hard for her to draw the line between their private life and the band itself because. “The band’s always there,” she says. “In a way, our private lives do come into the band, but it’s not in a very obvious way.” She giggles again. “I mean, we’re not often going off and snogging together before the gigs or anything. At least I don’t think so.”

She turns to Googe: “Do we do that?”

“I dunno,” Googe says, slightly annoyed at the question. “It’s not obvious if you do. I think I’d notice.”

Shields describes Butcher and himself as a “typical band couple” — as opposed, say, to those “normal” couples. “I mean, we’re together so much,” he says. “Normal couples aren’t together all the time. When you’re in a situation like this, you can’t live the life that other people live. You haven’t got the same freedoms. I mean, you have different freedoms. But, like, we can’t just go out and say, ‘I gonna do this for a while.’ Can’t do that. Everything is tied into what we are doing with the band. But we don’t talk about the band when we’re alone, really.”

Athough Butcher was the last to join the Valentines, today she practically defines the group. It’s not that she’s strikingly beautiful, in a quirky, arty way — though she is. And it’s not just because, as one British music writer once noted, “she has eyes you could get lost in, and it would take you days to get out” — though that’s true, too. Butcher’s presence in the band is more enigmatic than that.

Bilinda Butcher in 1989. (Photo by Graham Racher)

Bilinda Butcher in 1989. (Photo by Graham Racher)Her vocals supply the often-cited ethereal quality that launched a thousand new British indie bands who co-opted My Bloody Valentine’s sound — like Lush, Chapterhouse, Ride, Slowdive … and the list goes on. It’s a soft, airy voice which acts as the wind in the Valentines’ turbulent tunnel. Shields and O’Ciosoig often sample her voice so they can regurgitate it digitally as the sound of a flute or other woodwind instruments. “It gives it the texture of a human voice,” Shields says, “but doesn’t sound particularly human.”

Butcher’s omnipresence in the group, together with her amiable, soft-spoken manner and blurred, pretty voice, has made her the unsought target of obsessed admirers. In L.A., a young, Morrissey-like fan leapt onstage during one song and hugged her. It was an awkward moment.

“It happened before, and it makes me confused,” she says. “I don’t know whether to start playing the guitar or… hug them back. I don’t know why they do it. It’s like they just don’t know quite what to do. It’s like they get there and realize there’s a guitar in the way.”

“And they’re up in front of loads of people,” Googe interrupts. “They don’t know quite what to do with themselves.”

“For a second, they just seem a bit lost,” Butcher continues. “It’s quite sweet, though; it’s funny.”

Shields sees it a bit differently. It’s not that he’s jealous, it’s that he’s a bit protective — of her and his surroundings. “It’s slightly unnerving, but I don’t think it’s meant as harassment,” he says. “In that sense, I don’t mind it too much — as long as they don’t stand on the effects pedals, I hate it when they do that. But it is unnerving, because you never know what somebody’s going to do. You don’t know what kind of person they might be. ‘Cause someday someone could just walk up like that and” — he pauses, hardly daring to articulate the worst — “like, knife you or something.

“But anything is possible,” he continues, “so I definitely wish someone would invent some kind of super-duper radar thing so that if anybody was to walk in with any kind of weapons, they couldn’t get in.”

Metal detectors, at a minimum, would have been particularly handy at a My Bloody Valentine performance in Germany, where the group performed a free concert before a dubious crowd. When they segued into “You Made Me Realise,” Shields got scared. “There were guns and drug addicts everywhere,” he says. “That time I was genuinely frightened. There were dodgy people all over the place. It was a bizarre crowd, the weirdest crowd we’d ever played for. It seemed like a brave thing to do to play that song at that show, but generally it’s not bravery, really, it’s just a bit intense.”

That’s true of all of My Bloody Valentine’s music. At a time when “ethereal” has become the latest marketing catchword for a musical scene in London that’s taken to celebrating itself, as they say, My Bloody Valentine has kept a distance from the crowd. During the two years it took them to record Loveless, other groups have incorporated the Valentines’ techniques — but not its intensity.

On Lush’s new Spooky, the group merely hammers out a set of light pop songs with neatly plugged-in dissonance. In contrast, My Bloody Valentine has carved out a whole new territory of musical textures. “I don’t like to talk about Lush because they’re all friends of mine,” Shields says, “but, like, we were doing this before they even knew what they wanted to do. I know that we would exist as we are whether this kind of music was hip or not.”

But the Valentines didn’t invent the stuff. “I’m definitely influenced by Sonic Youth,” Shields admits. “They did an awful lot in terms of groundbreaking. Their attitude towards guitars paved the way for a lot of people — a hell of a lot of people. We get a lot of credit for being influential in England that they never got and deserved.”

My Bloody Valentine has carved out a whole new territory of musical textures.

THE VALENTINES ALSO WERE INFLUENCED by the Cocteau Twins, although Shields’s guitar textures are much richer and more inventive than those of their forebears. Shields and O’Ciosoig have extended the boundaries of what mundane devices such as sequencers, samplers, guitars and drum machines can do. “I like music that’s inventive,” says Shields, “and I find that a lot of the current guitar bands in England who are influenced by the Cocteau Twins are quite uninventive. They’re happy just to plug into a pre-programmed effects thing and make weird guitar sounds. I like to abuse the effects, to use them in ways they’re not supposed to be used.”

He also likes to combine modern computer technology with old-fashioned effects boxes — a daub of Hendrix with a pinch of Public Enemy. “A lot of the digital stuff has these pre-programmed beats,” he says, “and rarely do you come across something that’s pre-programmed that doesn’t get boring real quick. After five minutes, it’s like, ‘Uhh, God, I’m sick of it.’ Also, a lot the digital effects have built-in protective circuits where, if you try to overload things, it just stops. Whereas if you’re messing around with the more analog-y type devices, they’re just more open to abuse.”

That gives My Bloody Valentines’ music an older psychedelic feel filtered through ’70s art rock and punk rock, but with more comtemporary ideas about rhythm, melody and dissonance. It has all the elements of older music without having to live in the “classic rock” ghetto. “It’s funny,” Shields says, “the world has gone into this weird, like, time warp. You watch TV and hear people condemn bands for their ’60s-isms, but it’s honest, because we still hear that music all the time. It’s not like we’re trying real hard to search it out and be retrogressive, it’s just that it’s always there in front of everybody’s faces. It wasn’t that way back in the ’60s and ’70s; the music of the ’30s and ’40s wasn’t in everybody’s faces back then. Modern-ness is down to context now more than the actual material that you’re doing.”

Shields would like to see My Bloody Valentine’s sound put more in the context of hip-hop and grungy American rock than in England’s so-called “dream pop” trend. “I realize that hip-hop is very modern music in a way that ours isn’t,” he says. “If people in the ’60s were to hear us, they’d go, ‘Wow, that band’s kind of weird.’ It might seem alien to them because of the technological precision-ism in what we do. But we are in a machine age, so we kind of naturally imitate those machines. So that side of us would seem alien when put beside the Velvet Underground, who were all loose and flowing.

“But if you played hip-hop or house music to a ’60s audience, people would go, ‘Wow! That’s weird, avant-garde wildness!’ And that’s kind of strange, because in the ’90s, it’s totally commercial music. So, in that sense, hip-hop and house music is more modern than what we’re doing; not that what we’re doing is less relevant. It’s realness that matters, and in England, it’s trendy to be modern — to be hip-hop or house or ethereal, or this or that — whereas in America, it’s pointless to be trendy.”

But how does all of that fit in with the music My Bloody Valentine makes? “Well, it’s not in the exact beats — though we do use some of the beats because they are good rhythms and suit what we do — it’s more in the attitude.”

In sharp contrast to Morrissey, who announced last year in these pages that “dance music has killed everything,” Shields has another view. “Dance music has done a hell of a lot for people’s perceptions of tune and hearing — of what it means to be ‘in tune.’ There’s a lot of out-of-tune stuff in dance music because they just pile samples on top of each other which sound real good together, but are way off key. But because the bass is turned up so loud, you can’t hear that it’s off key. That stretches people’s attitudes towards what is right or proper.

“Dance music helps us,” he says, “yet we have fans who hate dance music, and that’s really frustrating. I tell them, ‘It’s good. Just listen to it.’ I think a lot of people don’t realize that [dance music’s] helped them to like us. It paved the way for us. I guess it’s just that when some things are popular, people tend to react heavily against it. To me, that’s kind of silly; you’d think that people who listened to this kind of music would be more open-minded. Yeah, right!”

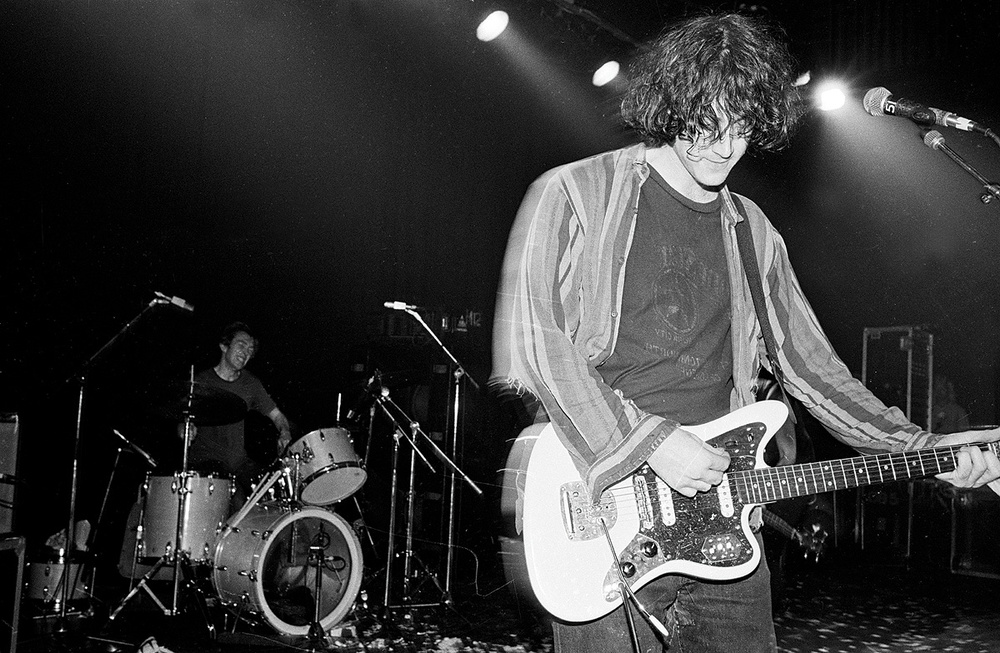

My Bloody Valentine blows a noisy kiss on stage.

My Bloody Valentine blows a noisy kiss on stage.IT’S DIFFICULT TO DESCRIBE being in the middle of the pounding, incessant noise of My Bloody Valentines’ “You Made Me Realise” unless you’ve actually seen the band live. After about 30 seconds the adrenaline sets in; people are screaming and shaking their fists. After a minute, you wonder what’s going on. Strobe lights are going mad, and you begin to feel the throbbing in your chest. After another minute, it’s total confusion. People’s faces take on a look of bewilderment. The noise starts hurting. The strobes start hurting.

The noise continues.

After three minutes, you begin to take deep breaths. Some people in the audience stoop down and cover their ears and eyes. Anger takes over. A few people leave the room. After about four minutes, a calm takes over. The noise continues. After five minutes, a feeling of utter peace takes over.

Or violence.

“For some peolple,” says Shields, “it’s hypnotic. It’s very organic. Others can’t deal with it. It’s just too much for them. For me, it’s total experimentation, completely relaxing. I like watching what happens; looking at people and watching their reactions. Sometimes it’s amusing and sometimes it’s scary. It says a lot about people.”

© Mark Kemp, 1992