In the mid-1980s a ragtag group of folk musicians led by the one-named singer-songwriter Lach, along with Roger Manning, Cindy Lee Berryhill, Kirk Kelly, Michelle Shocked and a few others, forever changed the way we’d hear acoustic guitars and passionately sung vocals. They called themselves “antifolkies.” I wrote about the collective back in 1988, and within a handful of years, a few stars began to emerge from the scene — John S. Hall’s King Missile, Regina Spektor, Jeffrey Lewis, Kimya Dawson’s Moldy Peaches, and Beck. But this is where it all began.

New York City ‘antihoots’ inject punk energy into the time-honored tradition of acoustic protest music

By Mark Kemp, Option, Nov/Dec 1988

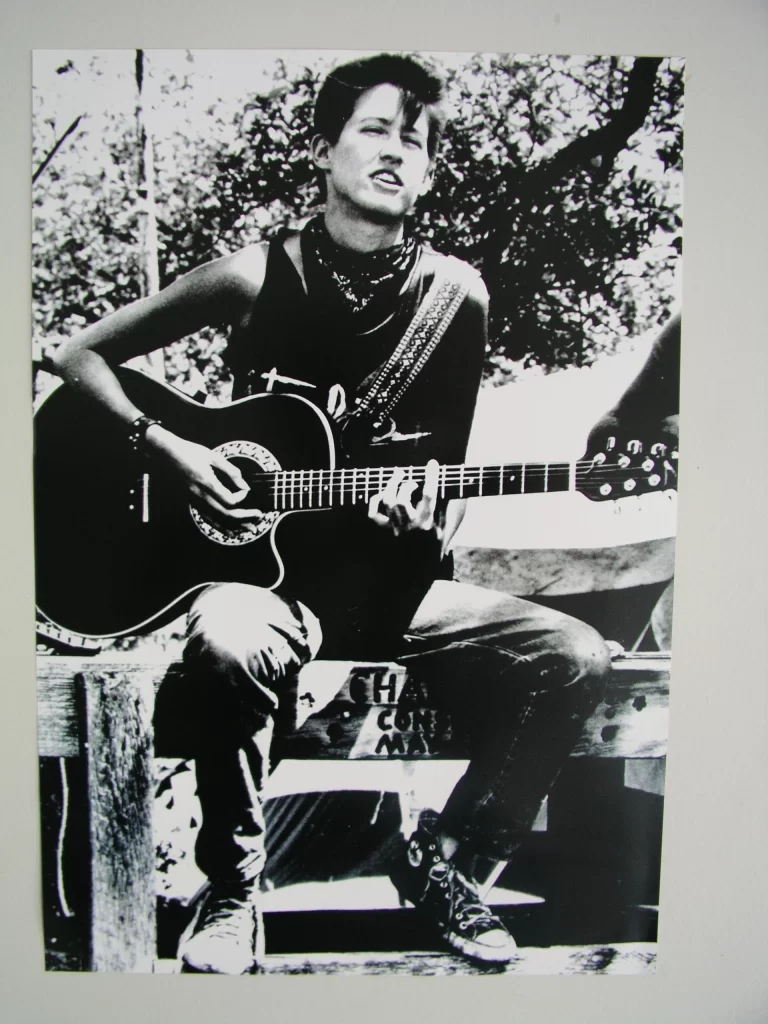

IT’S ANOTHER SWEATY late-June Friday in New York City, and Michelle Shocked is walking eastward across Chinatown’s busy Canal Street. She’s wearing a faded black sleeveless T-shirt, black jeans, black Converse Chucks, and a black cap. A boyish looking woman whose hair is as black as the clothes she wears — and very, very short — Shocked is in town to do a benefit concert for the homeless, and to finish some last-minute promotional work for her second and latest release, Short Sharp Shocked.

Later, onstage at CBGB, this tough-looking woman in black appears quite the same as she does this afternoon, only her music might not sound like what you’d expect. She sits casually with her legs apart, a Yamaha acoustic strapped over her shoulder, and picks and sings traditional yet vibrant folk songs about traveling: of quiet nights in Amsterdam and Texas and San Francisco; of conversations with old sailors and stories about rich hobo hitchhikers. On “The Incomplete Image,” from her 1986 debut The Texas Campfire Tapes, the singer meanders a cappella through the song in a talking-blues style and then fingerpicks country-blues melodies between each verse.

Released on England’s fledgling Cooking Vinyl label, The Campfire Tapes was recorded spontaneously on a Sony Walkman as Shocked sang her tunes literally beside a campfire at the Kerrville Folk Festival in Texas. On her latest LP, she throws a few curves, packing everything onto the record from a fat jugband sound to old-style R&B, a smidgen of jazz, and, yes, even the sort of hardcore slam-bang you’d expect from this woman covered in punk regalia. “Fogtown,” which isn’t listed on the cover, is a punk-rock remake of a tune from Campfire Tapes, originally done soft and rhythmic with just her acoustic guitar.

I’d spend half my time at the Fort and half my time at CBGB with the skateboarding hardcores. — Michelle Shocked

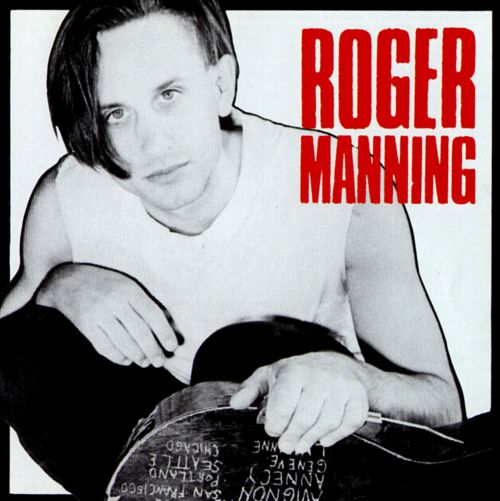

Shocked isn’t alone in this contradictory mix of traditional folk and noisy post-punk. A growing group of similarly postured young urban folkies have gathered on New York’s Lower East Side — a group of folkies who, five years ago, decidedly broke the umbilical cord that had connected them with the long-dead 1960s Greenwich Village urban folk scene. Among this group are Lach (pronounced “latch”), the scene’s prime organizer and a songwriter in his own right; self-defined “folkgrass” singer Roger Manning; Long Island native Kirk Kelly; and California-bred Cindy Lee Berryhill. You could call this new species of folkies neo-bohemians: They rap like Jack Kerouac (“we’re gone, baby; like beat, ya know…”), perform like Woody Guthrie (acoustic guitar, harmonica, wailing vocals), and dress like Stiv Bators of the Dead Boys (tight black jeans, black belts with silver studs, black combat boots, black leather jackets, black, black and more black). They fight the growing gentrification of their neighborhood, their motto is “Go Man Go,” and they’ve named their new musical habitat the “antifolk scene.”

It would be easy to blame R.E.M. for this growing fascination with folk (and why not, they’re blamed for everything else?), as Michael Stipe and company very well might have generated a new interest in rootsy rock’n’roll. But more likely it was Suzanne Vega’s early success that fostered this re-creation of a new urban folk scene. Although she wasn’t actually part of this particular Lower East Side folk gang, Vega’s rise to the pop music pantheon produced something of a domino effect: Polygram seized Shocked, Rhino nabbed Berryhill, SST captured Kelly and Manning. But the antifolkies are grittier than Vega — and less polished than Boston’s Tracy Chapman, this year’s mainstream-folk success whose self-titled Elektra debut has gone to the top of the pop charts.

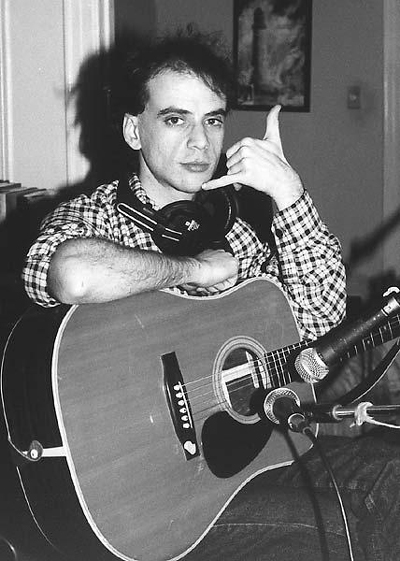

IT’S 6 P.M., AND LACH is preparing the lineup for tomorrow night’s hootenanny at the Chameleon club on 6th Street between avenues A and B in the East Village, an event he calls “Lach’s Lair.” He’s the backbone of this new generation of urban folkies who were cast away from the tired West Village scene simply because their aggressive songs teeter on the tightwire between the two musical worlds they grew out of — that of Bob Dylan and Phil Ochs, and that of the Ramones and the Clash. Lach provided the first Lower East Side performance space that dared to cater, he says, to “anybody who wanted to be heard.”

For the entire antifolk gang, the momentum began when Lach got kicked out of his Greenwich Village apartment. Simultaneously, he had been functionally banned from most of the legendary folk clubs, such as Folk City and the newer Speakeasy. “The rebellion just grew and grew,” Lach says. “I was living on the west side, on Bleecker and MacDougal, in an illegal sublet at the time.” The area seemed an appropriate abode for Lach, considering that that very corner was the geographical heart of the ’60s folk scene. “So, these were my local clubs,” he says. “And I stayed with it for a while, but it just wasn’t happening. We’d get up there and play our songs loud and fast, and they just put a lock on us.” It was hinted to some of Lach’s mates that if they continued fraternizing with him, they would be barred, too. “It was crazy, the amount of backbiting and incest going on,” he remembers, shaking his head.

So Lach scoured the real estate pages of the Village Voice and found a 700-square-foot loft space on Rivington Street on the East Side — for $600 a month. He moved in, built a stage in the middle, and added a small bar at the back. Every weekend, the Hidden Fortress shook with the throbbing grind of Ramones-charged yet traditional-inspired folk songs. From 11 p.m. until dawn, people would play solo, en masse, a cappella — whatever. “We’d play all night, just whenever the party ended.” Lach recalls. The storefront afterhours club eventually became known simply as “The Fort.” “It was totally illegal,” Lach admits, “but what’s legal in New York?” And not only was the club illegal, it was on what the New York Daily News had recently rated as the most dangerous block in Manhattan — the lowest of the Lower East Side. “Yet we were packing it every weekend. And these guys at Folk City were talking about not making enough money from folk music to stay alive.”

The Fort finally faded, but “Lach’s Lair” at the Chameleon club has carried on the same free-for-all tradition. And the crowds are growing. Lach always performs a song or two of his own, such as his alliterative, Phil Ochs-styled “Positions of Power,” the whiny “John Glenn Song” (“I wanna be an astronaut. I wanna fly through space…”), and his partially syncopated, reggae-influenced “Poet Strike.” On some nights, you’ll catch Manning or Kelly or Berryhill there, and there’ll always be scads of new kids on the folk-music block.

Lach scribbles a few names on a scrap of faded notebook paper, peers up through thick-rimmed black glasses, and grins. “I always wait till Friday to get my shit together for the Lair,” he says, as he wipes small beads of sweat off his brow.

But are Lach and company just a coterie of young copycats attempting to revive two bygone generations — that of the ’60s Village folk scene and that of the punk/new wave movement pioneered at CBGB in the mid-’70s? Or are they a genuine musical force, harvesting new, exciting alternative music from a traditional mold?

“What’s not derivative in some way?” asks Manning, whose self-titled debut gracefully juxtaposes hard-strummed, rootsy songs with softer, fingerpicked bluegrass. “Folk, punk, bluegrass — I like to call what I do ‘folkgrass.”‘ But there’s something that distinguishes Manning from both Bob Dylan and Bill Monroe. The LP has all the flavor of Manning’s “folkgrass” influences plus lightning-speed, Sex Pistols-like chord changes that charge each verse of, say, “The Lefty Rhetoric Blues,” a tune in which Manning sarcastically condemns and then skeptically compliments old leftists for spouting boring, oversimplified political rhetoric.

“They gotta be fools to think they can get a sympathetic ear here,” Manning chides, as his fast, rhythmic acoustic chops flutter away chaotically at the ends of each verse. “Lefty folksinger rhetoric has such a boring ring. / They make me sick. / It’s either ‘no more bombs’ or ‘no more nukes.’ / But then, on the other hand, they were right about Vietnam…”

Manning debuts such tunes in New York’s frantic, screeching, oven-hot subway stations. The slender, dreamy-eyed singer straps his battered Yamaha acoustic guitar around his neck and sings songs of protest and lost love in a carefree, sometimes wailing, and sometimes talking tenor voice. He sings to the myriad of people who pace filthy subway platforms waiting for trains to Wall Street, SoHo, Chelsea, or Harlem. He doesn’t play for the money — you don’t make that much much — but for kicks.

“You know, down there [in the subway], people really listen,” he says. “I mean, this is New York City, and down in the subway, I’m racially in the minority most of the time. Yet most of the folks, no matter what persuasion they come from, will listen to me…” — assuming that a train isn’t thundering by.

In “The West Valley Blues,” Manning scorns “a new generation of racist fools.” And like his folksinger predecessors dating back to the turn of the century, in his talking-blues tunes, he’ll drop a few names of friends, such as Michelle Shocked, his labelmate Kirk Kelly, or Cindy Lee Berryhill.

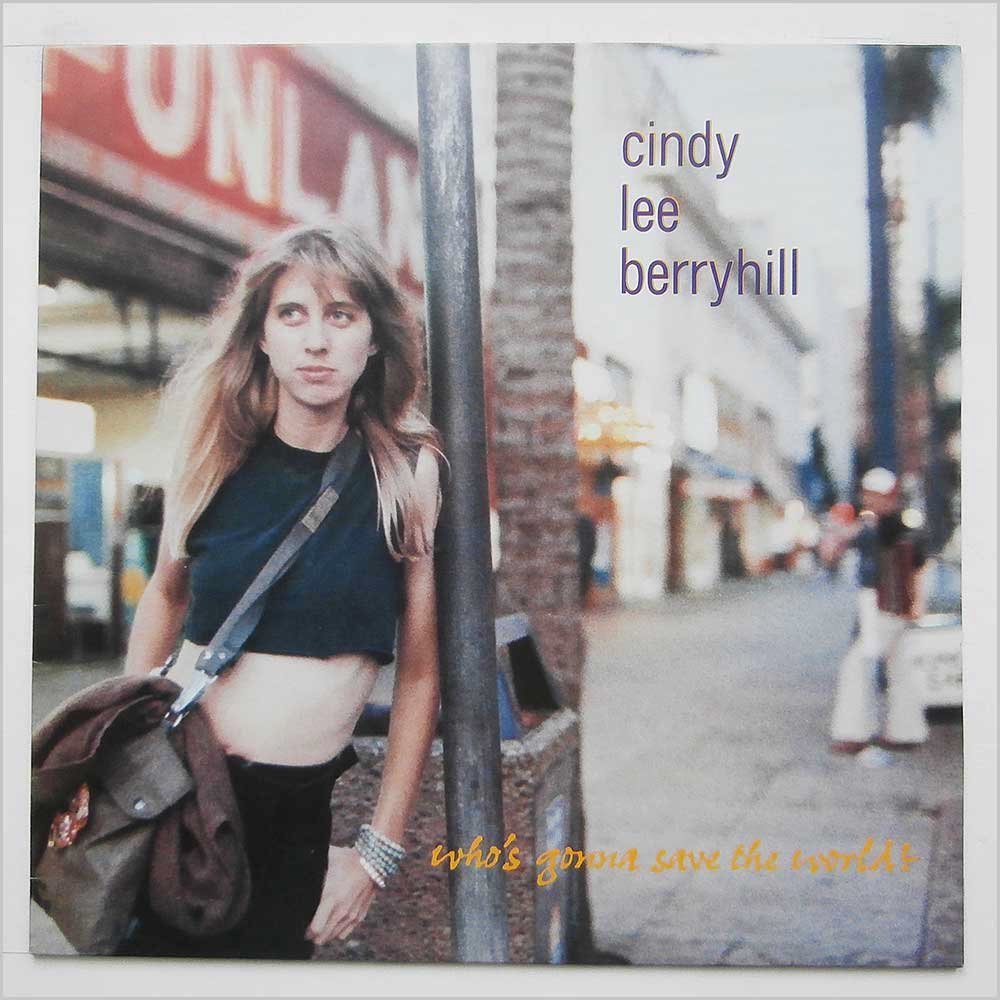

IF IT’S 6 O’CLOCK in New York, it’s mid-afternoon in San Diego, where Berryhill, who pointedly defines herself as a “New York musician,” is likely strumming her Yamaha and wishing she was back on the east coast. On her 1987 debut, Who’s Gonna Save the World?, Berryhill sings subtly feminist tunes in an often callow manner – though not without humor. In ‘Damn, Wish I Was A Man’, she sarcastically yodels the title. At other times, though, Berryhill wails stream of consciousness expressions more in the style of Patti Smith or Sinead O’Connor. Onstage, the blond Californian tends more often to lilt freely about lost friends, garage band meetings, or the atrocities of Reagan-era politics.

Who’s Gonna Save the World? has its share of clever speed-poetry phrasing. “Whatever Works” begins in a jive, talking-blues style, Berryhill chiding folks who calculatedly write songs in posh skyscraper offices. And in “Looking Through Portholes,” which has a catchy Ian and Sylvia-like pop refrain, she sings of “old ghosts and Chagall shapes, beat subterranean haunts, long gone daddies…” The record’s Velvet Underground dirge is “Steve On H,” a long, hard, piercing piece in which Berryhill muses on drug addiction. The song begins with her flighty voice sounding innocent, but climaxes in a vocal frenzy, encompassing the styles of both Smith and Kate Bush along the way.

However New York Berryhill would like to think she is, the LP still has a clearly California feel, though perhaps with heavy touches of east coast consternation. It’s a tapestry of ironic humor and devastation. “I’d be sexy with a belly like Jack Nicholson,” she sings in “Damn, Wish I Was a Man,” and then a fretless bass mimicks the sound of a beer gut (booooOOOOOOoooom). ‘She Had Everything’ is a steady-paced, bass-dominated, and ironically pop-like tune about a suburban friend who’d killed herself for obviously unstated reasons. “She had a Cadillac car, thought she’d go far, real smart…”

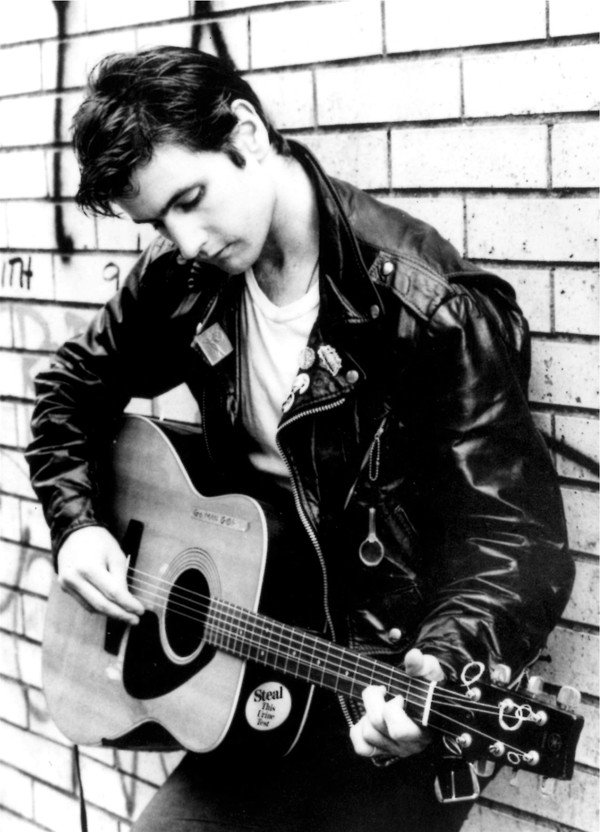

Back in New York, it’s still around dinnertime, and Kirk Kelly — who rarely goes out dressed in anything but faded black jeans, a flimsy white T-shirt, and a secondhand gray vest emblazoned with a button bearing the face of his hero, Ochs — also sits alone, tuning his Yamaha. Kelly’s preparing for the benefit concert he’ll do on Saturday along with Shocked. He’ll perform his rapid-fire political anthem “Working in the Vineyards,” in which the song’s protagonist “puts in an honest day’s work for a half a day’s pay.” Chances are, Kelly’ll also do his nasal-voiced ode to Ochs and others who’ve influenced his life and music. In a slow, steady tempo, he strums the song’s chords and asks, “Who’ll be the heroes of tomorrow?” Not surprisingly, “Heroes of Tomorrow” is stylistically very similar to Ochs’ own “A Toast To Those Who Are Gone.”

It makes sense that Kelly’s songs would sometimes mimick Ochs’ in style, politics, and aggression. Unlike most of the others in the antifolk family, Kelly came to folk music via folk music itself — not via the Sex Pistols. His family home had bins full of old Irish music, so when Kelly received his first Dylan record, it was an easy transition to songs of social justice. Writing labor-organizing anthems like “Working in the Vineyard” came naturally, Kelly says. “I just sat and listened to that first Dylan record I got,” he says. “I mean, I’d heard the same sort of stuff on those old Irish records.”

Kelly is terribly aggressive onstage; he injects squalling, Dylanesque harmonica into most of his songs, and during a live performance at CBGB once, he pounded so hard on his guitar that he broke three strings during just one song. The tune was “Go Man Go,” the title track of his recent SST debut, in which he shouts in a scratchy voice, “Don’t look back!” (Another Dylanism, perhaps?) In the wry “Red Blues,” he bangs out the song’s three chords and screams sarcastically, “I don’t wanna be no Communist / Those damn liberals get me really pissed / Don’t they know we could be next? / I don’t wanna be no Communist.” Then, he utters, “Take it away boys” — the “boys” being himself and his own mouth harp. Go Man Go was produced by Brian Ritchie of the Violent Femmes, punk’s first set of crossover folkies. Ritchie also plays acoustic bass on one song.

God, I remember times when we’d sit around all night long and sing and trade songs and talk about Phil Ochs. — Cindy Lee Berryhill

During the mid-’80s, while Lach, Kelly, Manning, and others in New York were begrudging the West Village oldtimers, Shocked and Berryhill had wandered on to the scene separately and serendipitously. Berryhill breezed into town searching for people to share ideas with. “Lach had started those Fort nights before I got to New York. But when I got here, he’d quit doing them,” explains Berryhill, whose upcoming Rhino LP will be produced in New York by former Patti Smith guitarist Lenny Kaye (who was Suzanne Vega’s producer, too). “I persuaded him to start the Fort up again, and then I decided we should all get together — all of us who were being shunned by those West Village people; all of us who were wearing combat boots and playing acoustic guitars; all of us who had grown up with the Buzzcocks and the Clash — and do an antifolk festival.”

Berryhill never expected to stay in New York for more than a week or so. “But when I met those guys, and this whole group of people with all this spirit, I knew this was where I was supposed to be,” she says. “God, I remember times when we’d sit around all night long and sing and trade songs and talk about Phil Ochs; talk about putting together a magazine and not having to rely on that burned-out, boring West Village scene — talking about, ‘We can make our own scene!'”

Shocked moved to the area in search of that same communal atmosphere — freedom of expression, a more politically responsive community, and diversity — but she felt caught between two groups. “Here, I’d spend half my time at the Fort and half my time at CBGB’s with the skateboarding hardcores. Having been among the hardcore and acoustic scenes in Austin, I had much higher standards of politics than the (East Village) ‘boy’s club’ did.” That “boy’s club” — with “boys” such as Berryhill, Sarah Hauser (a performance artist/folk rapper), and Kristen Johnson (publisher of X-posure fanzine, the contemporary equivalent of popular ’60s folkzines such as Sing Out! or Broadside) would likely differ with Shocked’s characterization of the scene. Nevertheless, after her 1986 release, Shocked became something of a troop leader for the antifolkies.

Though now nominally based in London, Shocked still considers herself a part of the Lower East Side antifolk scene, although she does more traveling than remaining settled anywhere. In addition to Austin and New York, she’s lived among squatters in San Francisco. In Amsterdam, she was homeless and free, which inspired “5 A.M. In Amsterdam,” a beautiful, soaring tune on Campfire that rings with crisp fingerpicking and lyrics about the simplicity of “living alone now,” not dependent upon telling time via wristwatches, but by observing nature and listening to the rings of distant church bells. As the Campfire record spins, you can actually hear crickets chirping in the background. Although Shocked’s roots lie in the rural south, she switches easily to the urban-folk mold. On “Graffiti Limbo,” from Short Sharp Shocked, she sings of a young black man who was strangled by New York transit cops simply for spraypainting art on the city’s putrid subway station walls.

“I remember first seeing Lach perform at Folk City before it closed,” Shocked says. She’s sitting back in a rickety chair at a Greenwich Village restaurant only a stone’s throw from Washington Square Park, where a quarter-century earlier, Dylan and Ochs would play for free. “Then I actually met Lach at Speakeasy. His energy was so different from most of the crap that went through there — I mean, Lach actually had energy.”

[The Fort] was totally illegal. But what’s legal in New York? — Lach

AS THE SUN SLOWLY RISES above a jagged East Village skyscape, Roger Manning is still awake. Sitting on a stoop on 11th Street and 2nd Avenue, he strums in minor chords the melody of a bitter song he wrote about sex and love and relationships in the urban America of the 1980s. Four of his friends sit cross-legged around him. Manning begins “The #17 Blues,” a Lou Reed-like talking-blues song, although in a softer, more storytelling manner than Lou would do it. “Jimmy says, ‘I don’t want no girl that wears leather like that,'” Manning sings, nonchalantly. “Me, I don’t care, so long as she don’t smoke while I’m sleeping.”

The front page of a New York Times tumbles by on the sparkling sidewalk and the song fades into the black. “Guess it’s time to hit it,” Manning suggests in a whisper. And the faithful, five-strong group of latenight folkie stalwarts nod in approval. After a few murmured farewells, they disperse into the foggy New York Sunday morning. They all have to get at least some rest tonight, because tomorrow there’s gonna be another hootenanny on Houston Street.

© Mark Kemp, Option, 1988

————————————————

On his debut album of 1988, Kirk Kelly asked in one song, “Who’ll be the heroes of tomorrow?” In the more than three decades since the birth of the antifolk movement, numerous artists have stepped up to answer his question. Here’s a playlist featuring a few of them, including most of the originals mentioned in this story: