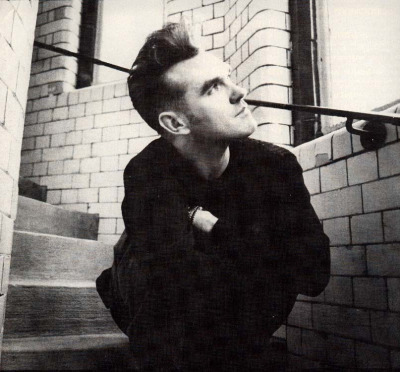

In 1991, my then-girlfriend and I flew from New York to London, then took a train up to Manchester to meet with former Smiths frontman Morrissey. This was years before the singer’s disturbing anti-immigrant comments and bizarre backing of a white nationalist political party landed him on the list of cancelled artists. At the time, everyone just considered Morrissey eccentric. My conversation with him was a hoot, and his poses for my girlfriend’s photo session in the stairwell of the Midland Hotel were revealing of a guy whose poses were important to him. After the interview and session, he invited us to Liverpool for a concert by some band whose name I can’t remember. We were extremely tired after our red-eye flight and long train ride, so we respectfully declined. “You’re going to pass up an opportunity to go with Morrissey to the town that gave birth to the Beatles?” he asked, incredulously. I later kicked myself for not going, but now I’m glad I didn’t. I wouldn’t want my first trip to Liverpool forever connected to the man Morrissey eventually showed himself to be. Still, this story is instructive: In retrospect, you can see the seeds of his racism in his comment, “Dance music has destroyed everything.”

Manchester is 185 railroad miles north of London, linked by signposts that read Rugby, Birmingham, and Stoke-on-Trent; by sprawling misty green meadows, gushing streams, and a zillion grazing sheep. The city itself is a soot-gray mosaic of European architecture, from the high Victorian gothic of its majestic town hall to the palazzo warehouses that color its cobblestone back streets. Welcome to the cradle of the Industrial Revolution. Welcome to the home of the Hollies, the Buzzcocks, Joy Division, the Stone Roses — and Morrissey.

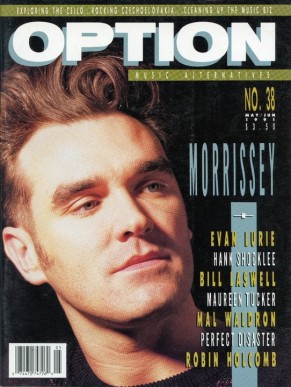

By Mark Kemp, Option, May, 1991

Sitting at a table in the lobby of Manchester’s famed Midland Hotel, the stately red-brick building on Mosley Street where C.S. Rolls and Henry Royce first met in 1904 to talk luxury automobiles, Morrissey is sipping herbal tea and feeling just miserable. That’s nothing new, of course, except that today, the former Smiths singer has a physical, tangible reason for it.

“Today?” Morrissey asks, raising his prominent eyebrows, dubious of my first line of questioning. “Well, let’s see. Today I’ve been suffering slightly because I’ve had a terrible bout of flu, which can’t be of any interest to anyone at all.” He puckers his lips to one side, forming an understated — and presumably unintended — Billy Idol-like snarl. It’s a shyer, more confused look, though; a look he tends to use often, particularly when faced with such taxing questions as, “What did you do today?” He continues: “I spent the entire morning covered from head to foot in phlegm, which is not” — he laughs — “terribly romantic.”

Morrissey, however, is terribly romantic. Despite his ostensibly non-romance-filled lifestyle — he’s declared his celibacy ever since The Smiths first surfaced in 1983 — Morrissey is a lot like the rest of us. He seeks the perfect relationship with another human being, though like the rest of us, he’s found it’s not so easy to come by. He’d like to be at peace with himself, though he’s had to move to the outskirts of Manchester to get it, away from all the oglers and hangers-on. He’s near religious about pop music, about that archaic belief in the popstar-as-protector, although after he himself became famous, his fantasy world was obliterated.

So now he fancies mere respect, although he’s routinely scorned by the British pop music press, which jumps at every opportunity to present him as a scapegoat all our human vulnerabilities. “I think people feel that if you live alone you are either incapable of having an adult relationship with other living, breathing human beings, or you’re just a very selfish person,” Morrissey sighs in his pronounced northern England accent, kind of like John Lennon’s, only the pitch is higher, and the tone more delicate. “I suppose that’s partly true of me — I do feel slightly selfish. At any rate, I go through these great gulps, these great patches of ostracization, and then suddenly lots of people pop up asking where I’ve been. Which is really quite nice.”

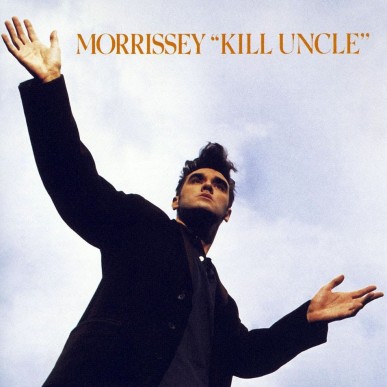

SEVEN YEARS AFTER the release of The Smiths self-titled debut and three years after the band’s demise, Morrissey is back in 1991 with Kill Uncle, his second post-Smiths solo album (not counting a singles collection, Bona Drag). Around Manchester’s busy Piccadilly Station, posters of Kill Uncle grace walls and note boards and the sides of buildings, along with ads for an upcoming G-Mex Centre concert by the city’s trendy techno-dance outfit, 808 State, and a few ominous announcements concerning the return of Uriah Heep — whoever that was.

Kill Uncle is a surprising treat from Moz — a solid and much friendlier group of songs than the lion’s share of his prior work. A few of his obligatory bummers and hoity-toity contempt for most of humanity lurk in the grooves — the album’s first single, “Our Frank,” has Morrissey singing, “Give us a drink, and make it quick/Or else I’m gonna be sick/All over/Your frankly vulgar/Red pullover.” But there are also songs like “Asian Rut,” a sensitive cry against racial violence in the U.K. And there’s the giddy “Sing Your Life,” a not-great song, but one which is downright good-natured in its call for people to do what he does — sing, that is. Such a song would have been unheard of during The Smiths’ reign, which indicates some kind of change and movement going on between Morrissey’s ears. “The older I get — and I’m now stumbling towards my 32nd year — I do feel happier,” he says. “There’s something about life that’s slightly easier; there are fewer expectations to be entirely and insufferably hip.”

Morrissey claims that if he were to quit it all today, “I would absolutely mind my own business. I’d live in a crumbling cottage somewhere in Somerset, out of the way. I would not try to claw my way back; I would not try to reinvent a ‘pop persona.'” He raises his head high, only partly mocking his self-importance: “I’m too saddled with dignity to do such a thing; I’m persecuted by a sense of pride and dogged by cunning foresight. It’s a shame, I guess — sometimes I wish I was just a simple drunkard.”

In 1984, The Smiths released their self-titled debut to generally chilly responses in the U.S., with the likes of Kurt Loder politely opining that their music “takes some getting used to.” In Britain, it was a smash, a welcome relief from the icy thud of mid-’80s synth-pop a la Spandau Ballet and the Human League. Guitarist Johnny Marr’s jangly riffs and hooky melodies, and the tight rhythm section of bassist Andy Rourke and drummer Mike Joyce, combined with Morrissey’s brooding lyrics and yawning voice to create a quintessential anti-pop pop sound, not unlike what R.E.M. was doing over on these shores. The music did take some getting used to — with Morrissey’s random forays into a shrill falsetto, and such bold out-of-the-blue lyrics as “Hand in glove/The sun shines out of our behinds” — but getting used to it was rewarding.

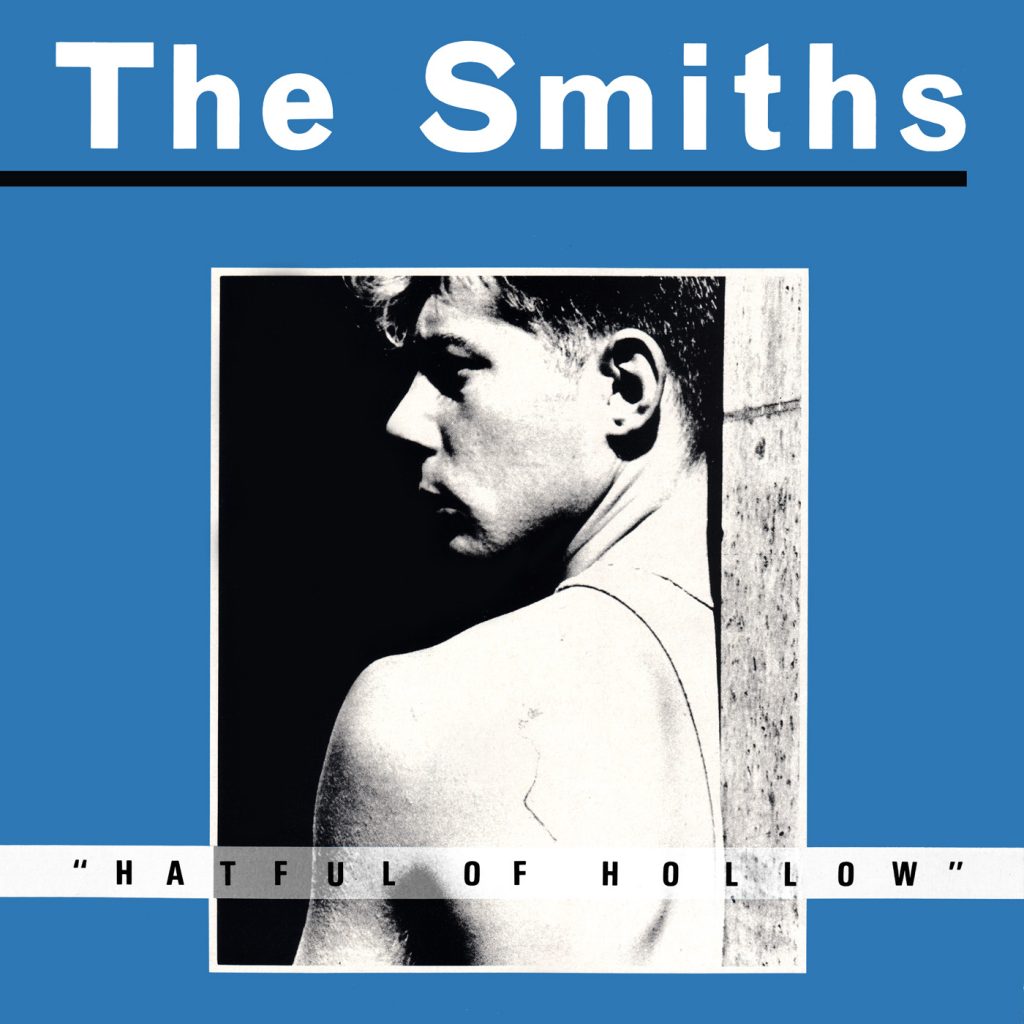

Their second album, Hatful of Hollow, was a collection of singles and remixes of songs from the first one. It fared better among critics, college radio, and indie scenesters in the U.S., but didn’t make a dent in the regular rotation (it didn’t help that The Smiths refused to promote themselves or do videos). With the release of their disappointing third LP, Meat Is Murder — and its single “How Soon Is Now” — a larger American audience started coming around to The Smiths’ charm, though reservedly. Their literal blend of indie-slash-pop never really did attract a mainstream audience here, but The Smiths earned a sizable cult following, releasing The Queen Is Dead in 1986 and The World Won’t Listen, the compilation Louder Than Bombs, and Strangeways, Here We Come, all in 1987.

Strangeways was the bitterest album of The Smiths’ already morose career; it sounded as if the players were just plain tired of all the criticism and hype surrounding their lead singer’s every move. Morrissey, too, was tired of it. As he sniffs on the new album, with his tongue hard in his cheek: “I don’t want to be judged anymore/I don’t want to be judged anymore/I would sooner be loved/I would sooner be just blindly loved.” On Strangeways, Morrissey had become consumed with the topic of death, singing of a dead discodancer, a dead rock star, a dead friend, and a “Girlfriend In a Coma.” The Smiths split after the album came out, and a live collection, Rank, was released posthumously in 1988.

Meanwhile, Marr went on to work with Bryan Ferry, Paul McCartney, the Pretenders, Talking Heads, The The — and most recently the British soul/pop threesome, Stex — while Morrissey started work on his first solo album, Viva Hate. The record featured big strings and a brand new sound, but it was less distinctive than The Smiths. Sadly missing were Marr’s shuffling guitar riffs and The Smiths’ smart indie-rock rhythm foundation. Morrissey accurately admits that The Smiths “had the best of Johnny and me; those were definitely the days.” But he proved on Viva Hate that he and other songwriters could pen at least some melodies that were as fresh and bright as those he and Marr had collaborated on — something few observers expected. “Suede-head” was a hoot, and “Everyday Is Like Sunday” remains possibly the best melody Morrissey has sung. Overall, though, the album was a bit bland and stiff.

While Kill Uncle has its uplifting moments, the material mostly remains in keeping with Morrissey’s wry, self-obsessed, hit-and-miss tradition, with song titles like “(I’m) The End of the Family Line,” “There’s a Place In Hell For Me And My Friends,” and one of his trademark wordplay songs, “King Leer.” Collaborating now with Mark E. Nevin of the band Fairground Attraction, the songs breeze along merrily enough, Morrissey lyrically highlighting his sense of humor rather than his utter melancholia. The album’s curve ball is “Found Found Found,” which is another not-great song, but a bombshell of sheer news. On it, Morrissey suggests he may finally have found someone to love. Behind brash, driving guitar rock, he gleefully sings, “Found found found/Someone who’s worth it in this murkiness/Someone who’s never seeming scheming.” Whether or not it’s a romantic love is still up for grabs, but one thing’s for sure: Morrissey, in that Morrissey way of his, is being charmed by another human being.

“It’s not necessarily sexual,” he says. “I don’t think I mention sexuality in the song at all. But even in the limited capacity of finding a real friend and realizing that it actually does take a lifetime to find one, I’m always slightly exalted by coming across someone with whom one has an instant rapport, an instant harmony.” After years of bewailing friendships gone awry, and people in his life who’ve jerked him around, Morrissey recently found at least one friend; one who, if not absolutely perfect, is at least perfectly understanding of his eccentricities.

Ironically, that friend is the equally eccentric Michael Stipe, whose own band, R.E.M., was a sort of musical and spiritual American version of The Smiths back in the mid-’80s. “Michael had written to me for a while and I was not quite sure what to think of his letter,” he says. “Then we met several times in London and went on these extensive walks in which we would just keep walking in huge circles around London and through Hyde Park. We just walked and talked and…” — he trails off — “…that’s always been very difficult for me. Michael is a very generous, very kind person.”

A Morrissey-Stipe musical collaboration sounds like a critic’s wet dream — and it just might happen. The two have discussed teaming up for a duet on England’s Rock Steady TV show. “It isn’t decided yet what we’ll do, but it would be nice to do something unusual, some Righteous Brothers-type thing, I’d like him to lead the way, actually. I think it could be one of those funny historic bits of pop television that’s so rare these days, especially in England.”

To be sure, Morrissey isn’t all fun and games these days. While outwardly he’s so calm he might as well fall asleep, inwardly Morrissey’s still compelled to drop the occasional impudent bomb or two, like: “I’ve always maintained that the human race is a great disappointment” and “There’s just no poetry in people.” And he still falls into the trap of playing into the hands of his potential detractors. But Morrissey has a droll sense of humor about him that’s all too often overlooked. At one point he delightedly confesses to having “had hot wax poured on my body on more than one occasion,” and then, without missing a beat, adds wryly, “in a critical sense, that is.” On one hand, his critics hate this sort of self-effacing arrogance; on the other, they can’t get enough of it. Even when Morrissey is quietly in between projects, the music press — particularly in Britain — refuses to leave him alone, endlessly conjuring up the name “Moz” for one moot connection after another.

BEFORE 19-YEAR-OLD JOHNNY MARR showed up at 23-year-old Steven Patrick Morrissey’s doorstep back in 1982, with guitar in hand and a yearning to form a rock group, Morrissey had worked as a civil service clerk, a hospital porter, and a record store salesman. He was incredibly unhappy. He had left school at 17, his life up to then always centered in one way or another around music, and now he had to do something with himself.

Morrissey had been possessed by pop music since 1965, when he bought his first single, Marianne Faithfull’s “Come And Stay With Me,” at only six years old. “I lost myself to music at a very early age,” he says, “and I remained there. Beyond the perimeter of pop music there was a drop at the edge of the world.” Even today, he sincerely believes his obsession with music was unlike anyone else’s in the world. “It’s so easy to throw that old word ‘obsession’ around. We often hear about, ‘Oh, I’m obsessed with this, I’m obsessed with that; I’m obsessed with music, I’m obsessed with theorizing about music.’ All of us secretly think we’re musicologists and that only we know what’s good and what’s bad. But the word ‘obsession’ — which is frequently applied to me — is a pretty dangerous one, really. I did fall in love with the voices I heard whether they were male or female. I loved those people; I really, really did love those people. For what it was worth, I gave them my life…my youth.”

“Music is like a drug, but there are no rehabilitation centers.”

Indeed, just before Morrissey joined up with Johnny Marr, he wrote a book about his beloved New York Dolls. “The New York Dolls were my private ‘Heartbreak Hotel’,” he says. “In the sense that they were as important to me as Elvis Presley was important to the entire language of rock’n’roll. To me, the New York Dolls were the best group ever to come out of America, and they were loathed by America at that time. Sadly, they were reasonably appreciated only after it was too late. The New York Dolls were an early version of the Sex Pistols, and if Americans and the American music industry had only been alert enough in 1972 and ’73, the New York Dolls could have changed so much. But not to be.”

When punk hit Manchester in the late ’70s, Morrissey was there. “I entirely embraced it,” he says. “It was a terribly exciting time. I was at all the right places at all the right times, and I saw all the right groups at all the right times. The Sex Pistols played their first show just three yards away from where we’re sitting right now, at the Free Trade Hall. It was a fantastic night. Nobody moved. People sat in awe. It was a very historic night, although I know it’s quite standard to look back upon rock history and say, ‘Oh yes, that was historic, it was moving, it was such a great night.’ And now that I think about it, it actually wasn’t. It was a dank night that only history has given a bit of color to. But those early appearances in Manchester by the Sex Pistols, and by the Buzzcocks, were truly, truly…er…I hate the word magical, but I have to use it, I suppose.”

Morrissey was 17 when his father, a security guard, divorced his librarian mother. Of his childhood and teen years, he is “hard-pressed to think of any pleasantries at all. I firmly believe that the past is what one is and what one remains to be. I’ve come to the conclusion that ‘it’ is here to stay, whatever that ‘it’ may be; the mold, the cast, has been discarded. I think that really speaks for all of us, too. I think our lives are so indelibly, irreversibly shaped at a young age that there’s very little we can do, although we always want to think that change is possible and that perhaps we’ll go through some magical transformation, especially with the arrival of 30 and then 40. But it doesn’t happen.

“It’s so abstract to me when I get letters from people who buy my records who weren’t even alive when I was watching David Bowie on stage. It’s that peculiar march of time. There’s a famous quote which goes something like, ‘You are what you are, having secretly become what you wanted to be.’ Maybe there’s some truth to that. We like to think that society shapes us, but I don’t think that that’s the way it happens.

“When I was young, I instantly excluded the human race in favor of pop music, and you can’t live a fulfilled existence like that. People are invariably there; you have to go to school; you have to try to communicate with those around you. But when you’ve sealed up your bedroom doors and you’ve blackened your windows, and all you want in the world are those tiny crackles that are about to introduce that record — and you love the crackles that you hear from the needle on the vinyl as much as you love what will follow — then I don’t think you will turn out to be a terribly level-headed human being. Music is like a drug, but there are no rehabilitation centers.”

Morrissey remains a rabid fan, though not of most current artists. “Tonight, on this very day that you and I are speaking, I will go home and I will play music very, very loudly, and I will be absolutely transported to a delightful new planet. I will listen to a record which I can’t stop playing at the moment: a single called ‘Good Timin” by Jimmy Jones — an old American MGM yellow-label record. It’s just simple, straight, boring, dull, floppy old pop music, but to me it’s…” — Morrissey lowers his voice to a whisper, his light blue eyes glaring straight forward — “…it’s like skin against skin; it’s better than fine cuisine.” He slaps his hand down on the table in front of him, and exclaims, “It’s better than sex! There, now, that’s how I feel.”

Morrissey still searches for old, obscure vinyl singles. “The seven-inch was — and still is — my reason for being,” he says. “I still collect old seven-inch records, although that’s obviously passing now” — due to the CD boom, an extra-sensitive topic for the already extra-sensitive Morrissey. “The death of vinyl is one of the saddest moments in pop history,” he laments. “It hasn’t happened here yet, but it’s happened in America, and I firmly believe that CDs are being forced upon us by money moguls who want consumers to have no choice but to buy them because they’re five times the price.

“The death of vinyl is one of the saddest moments in pop history.”

“But the pop single: there was just something about the pop single,” he continues. “The two-minutes-ten — the cramming of so much emotion into so little time — verses, chorus and fade out. All of the great Elvis Presley singles were under two minutes, and in those two minutes you just felt this tumultuous massive human sexual emotion.” Ironically — whether to annoy his fans or the heads of record companies or both — Morrissey has on more than one occasion subjected his own listeners to some of the longest pop songs. “Late Night, Maudlin Street,” for example, on Viva Hate, was an interminable seven minutes, forty seconds long. “Not all of them are long,” he says. “I recall that The Smiths made a record called ‘William, It Was Really Nothing,’ which was only two-minutes-nine. And we were heavily chastised by the record company for doing such a short song because Bronski Beat had released a record that same week which was 13 minutes long. There’s so much to fight against; it’s a terrible, terrible business. I hate the bruises.”

Morrissey’s passion for pop and his love of the stars who make the music have come back to haunt him. Each year, his faithful gather in Manchester for a convention to which they bring albums and posters, visit the Kings Road home of his father, and litter the city with gladiolas, the flowers Morrissey used to take onstage with him during Smiths performances and toss out to his audiences. As tormented as Morrissey says he feels about his own loss of youth to rock’n’roll, though, he doesn’t seem to care that others are losing theirs to him. In fact, he says, “It makes me feel honored that anybody would commit so much of their time thinking about what you see sitting before you. Their fantasies are largely inaccurate, but I obviously can’t visit them all personally, one by one, and straighten things out, as it were. Let’s face it, we all have our fantasies; most people fantasize about the programs they see on television, or about their sports fixations. There are probably a lot of people who quite like Dan Quayle.” To Morrissey, it was always the New York Dolls — that is, until Patti Smith came around. “They were my only friends. I firmly believed that. I knew those people intimately. I knew everything about their lives. Of course, I really didn’t, but in my own sheltered way I certainly thought I did.”

Morrissey’s infatuation with the pop star-as-hero pretty much waned as The Smiths gained success. That makes sense, but it doesn’t explain his utter contempt for practically all who followed The Smiths. While he still speaks reverently about his ’60s and ’70s idols, at one time or another he has condemned nearly every artist and band — from Prince and Madonna to the Stone Roses and Happy Mondays — that has appeared since the early days of punk. Except, of course, for The Smiths. “I still do believe that The Smiths were the best,” he says, undaunted. “I mean, in the general overview of contemporary Manchester music, examine the success of the Happy Mondays and…well, as far as I know they’re not successful at all in America. Look at the hysteria” — he rolls the word off his tongue — “that surrounds the Stone Roses, and compared with The Smiths they don’t have the songs. None of those groups have the songs or the spirit that The Smiths had, and they don’t present themselves in a new way. The Smiths were like nothing that had ever occurred before, and that’s a hard thing to do.”

He misses his old band. “It was a special musical relationship,” Morrissey says, “and those are few and far between. For Johnny and I, it won’t come again. I think he knows that; and I know it. Luckily, there’s still more on his part and more on my part to contribute. It was sad when The Smiths ended, but I don’t think there’s much that…” He laughs at his reminiscing, and adds: “I’m babbling, aren’t I? I’m swallowing my own teeth. It’s interesting to choke on your own words; it must be very gratifying for a journalist to see somebody choking on his own words.”

Morrissey’s thoughts about The Smiths stir-up overwhelming emotions. He tries again: “I guess I feel a complete sense of hopelessness about the demise of The Smiths. I think Johnny was very unhappy that he didn’t get an overwhelming degree of attention in the general assessment of The Smiths during their existence. There would be many, many album reviews which scarcely mentioned his name. And I feel that he wanted — that he needed — a stronger platform. He needed to be seen, and that’s been his aim since the demise of The Smiths.

“But that’s only one facet. I also think that The Smiths revolved too quickly, too constantly — it just never stopped. It was all very emotional: constant recording, constant observation, no guiding light at all, no managerial figures, nobody around the group who could offer a really useful, guiding — almost parental — hand.

“Johnny, even at the end of The Smiths, was very young. Apart from myself, all of the Smiths were very young. When I first met them they were teenagers and I was 22 going on 23; you know how vast a difference there is between being a teenager and being 22 going on 23? It’s a vast difference. I think The Smiths just snapped due to that kind of pressure, that boring old rock’n’roll pressure.”

IN MANCHESTER, you get two quid for four American dollars. Buy a pack of Marlboro Lights with that and you find that they have brown filters instead of the “normal” white ones. Stroll Piccadilly after ten on a Saturday night and you might get five conflicting sets of directions to one legendary, but now defunct, dance club. Hey, it’s a depressing city, but in spite of its perpetual bad rep — 19th century poet Robert Southey once wrote, “A place more destitute of all interesting objects than Manchester is not easy to conceive” — it’s actually faring better these days.

Publishing has returned, construction is going on in the heart of town, and on a good day the sun might peek out from behind the clouds. Which leads one to wonder what’s left here for Morrissey, who’s fashioned an honest living out of railing against his surroundings. “The Manchester landscape has been so over-documented by me in the past; it’s just so much a part of me and The Smiths’ foundation that I don’t feel I can repeatedly be photographed standing in front of warped signs. I live on the outskirts now; I’m no longer a familiar figure on the backstreets of Manchester. That part of me has moved on, moved away — and happily so.”

Over the past 200 years, Mancunians have given us not only the industrial revolution, luxurious cars and Morrissey, but also the modern working-class hero, the world’s first passenger railway station, John Dalton’s atomic theory, the social writings of Friedrich Engels, and — most recently — a slew of retro-psychedelic dance groups and mop-top rugby hooligans stoned on hip-hop beats, acid house, and cheap ecstasy. None of which impresses Morrissey. He’s disgusted with the trendy mop-top rugby hooligans who’ve stolen his press; he’s not particularly mindful of Rolls Royce automobiles (he happens to drive a ruby red Porsche 911); and he hates — absolutely detests, without apology — dance music. Which in 1991 in Great Britain — if not everywhere — can pretty much brand a fellow old-fashioned.

“I’m not so blind as to not be aware of that,” Morrissey admits, “but, believe me, I’m happy to be in that category. I could never, ever begin to explain to you the utter loathing I feel for — as you say — dance music.” He spits out the word like it was poison or something. “I think dance music has destroyed everything — it certainly killed the pop star. It is bought by audiences who do not care about the personalities involved in music-making.” As if that were so awful.

“I think dance music has destroyed everything — it certainly killed the pop star.”

By midnight on Manchester’s backstreets, lines of people form at the doors of places like Soundgarden, an all-night dance club which seems to be attracting much of the crowd that once frequented the Hacienda, the legendary Manc club started by Joy Division. By 1 a.m., the Soundgarden dance floor positively jolts with that familiar big American electronic drum bite. Quick-cut samples of Public Enemy, Technotronic — and of Manchester’s own 808 State — wriggle through the noise. The dancers are clad in oversized T-shirts, their bowl-shaped hair drenched and faces glowing, clearly fueled by ecstasy. Dance and “ex” are all the rage in Manchester these days — like punk never happened; like The Smiths never happened.

“I despise the advent of the 12-inch remix, the multi-mix, the dance mix, the etcetera mix,” says Morrissey. “It’s all just another nail in the pop coffin. For people such as I, who don’t take drugs, there’s no way that you could ever become involved in that scene; that you could even understand it. The structure of the song just doesn’t exist. It’s the basic line of the groove, and that’s all that’s required — along with a high voltage of drug intake. That’s the only experience. Dance records are generally made by people who are not sensitive, who don’t care about music, and who care nothing at all about the history of music. And to me that’s the most important element. They don’t care at all about the past; they don’t care about what has gone before.”

Of course, DJs who spend half their lives combing massive record collections for the best historical moments to capture for use as a sample might disagree with Morrissey. But that doesn’t faze him. “There was an opinion about four years ago that, ‘Oh, isn’t it wonderful that two people can sit in their bedroom in Detroit with a little bit of machinery and come out with this huge wall of sound.’ To me, the sadness is just that — two people sitting in one room surrounded by a bunch of machinery. To me, that is sterility at its utmost. I want to see real people onstage playing real instruments; playing them hard and feeling it. I despise the backbone of that dance beat which doesn’t alter at all in the American top 20. I find it totally shocking and revolting.”

He doesn’t think much of the more rock-oriented, psychedelic dance crowd, either. Ironically, the Stone Roses, whose danceable yet jangly sound echoes some of Morrissey’s ’60s faves, actually cite The Smiths as influences. Still, Morrissey is resentful; he passes them off as a mere “press creation.” Says Morrissey: “The Smiths were not a press creation like the Stone Roses, who are just so press created. The jingly jangly Roger McGuinn-ness of The Smiths was only one aspect of a lifestyle which was multi-faceted. And The Smiths made it on their own terms in their own way. Nobody helped us, nobody promoted us, and we didn’t even use video until our ninth single, which was a complete disaster. Up until then it was a private club that, in spite of everything and everybody, became successful.

“I feel shuddering disappointment at the current Manchester lot,” he continues. “It’s been entirely embraced by the nation as being the true and real face of Manchester music, and I can’t recall anything that’s made me feel sadder. Mainly because: A) there are no singers involved, no vocalists with strong tones; and B) there are no useful lyrical constructions. It comes down to that boring, turgid, tired, desperate old hat called ‘attitude.’ It is pure fashion and pure trend. Sadly, during The Smiths’ existence the music establishment in this country never, ever, ever, under any circumstances, accepted The Smiths. Then finally, at the time of The Smiths’ death, the country began to look at Manchester as being this hotbed of pulverizing new talent. Therefore, all the wrong groups found it very easy to slip through the net and become successful.”

Sometimes Morrissey thinks about what would happen if he suddenly lost it all. “Personally, I’ve always felt, at each moment, that it could shrivel away,” he says. “I still feel that. In making Viva Hate, compiling Bona Drag, and recording Kill Uncle, there was always a feeling that this could be the final moment. I think that’s something that stays with you forever.” He compares himself to a couple of Beatles: “It’s like Ringo Starr making that statement very early on with the Beatles; that if he could buy himself a little shop, he’d be the happiest person alive. And John Lennon saying if it lasted two years, he’d be happy. You always feel that you’re skating on the edge — that public taste could just go like that — and then suddenly you’re posting letters for a living.”

© Mark Kemp, 1991 (First published in the May 1991 issue of Option magazine.)

I was feeling anxious at 6 am this morning, depressed by the thought of another work week doing unfulfilling things for 9 hours a day and then I stumbled upon this article after trying to research a bibliography note in “Mozipedia.” Now I have no anxiety. I just have total affirmation. These 45 minutes have been a blissful escape. After each paragraph, I dreaded to scroll down and discover the article ending. Thankfully it took a long time. This was perfection, thank you Mr. KEMP.