“Ah, baby, you’re so vicious…”

Reading on Facebook today that Lou Reed had died, I had one of those visceral reactions. I literally felt it in my gut. It was as though someone had punched me. Hard. With a flower.

Lou Reed was too tough to die. He was too gentle to die. He was too mean to die. He was too compassionate to die. John Cale, his former band mate in the Velvet Underground, was the easygoing member. Lou was the prick. If you didn’t believe that, all you had to do was ask him.

I could go on and on here about how important Reed was to late 20th century American music, and how much of an influence — both good and bad — he had on me personally. And plenty of people will write those kinds of tributes. That’s because Reed influenced misfits like me all over the world — writers, poets, actors, artists, musicians. They’ll all be singing his praises, as they should. Much more gracefully and articulately than I.

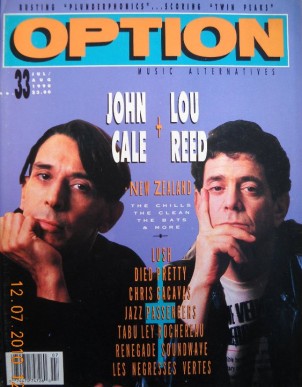

I’ll just say this: Reading the late great rock critic Lester Bangs’ interviews with Reed when I was a teenager made me want to write about music for a living. And I wound up doing just that. One of my earliest cover stories for a national music magazine was a piece on Lou Reed and John Cale about their 1990 reunion project, Songs for Drella, a requiem for their friend and mentor, Andy Warhol, who had died three years earlier. Rather than wax nostalgic with lachrymose tales of Lou Reed glory, I decided I’d just post that cover story here. It’s from the July/August 1990 issue of Option.

Rest in peace, Rock & Roll Animal.

15 Minutes with You

Lou Reed and John Cale perform a requiem for the late Andy Warhol

By Mark Kemp

The heckler’s voice sounded its fury like a cannon about midway through Lou Reed and John Cale’s performance of Songs For Drella, a pop requiem the two wrote in memory of their late friend and mentor, Andy Warhol. “Tell us something we don’t know,” came the gunfire.

It was opening night of the Velvet Underground co-founders’ first full-blown collaboration since Cale left the band back in 1968. Cale shrugged slightly at his piano stool. The audience packed inside the Brooklyn Academy of Music sat like jello. Everyone waited for Reed’s response. But there was only silence — no “fuck you,” no “go home and read a book, motherfucker.” Lou bit the bullet. He held his tongue. And this, my friends, is growth.

LOU REED leans forward in his swivel chair and rests his arms on a large executive’s desk. He stares slightly askew through a pair of wire-rimmed spectacles that are so respectable they’d earn Lee Eisenberg’s stamp of approval. Not one hair on his head is out of place, and the outfit he has on looks so spiffy you get the feeling it was picked up from a dry cleaner in SoHo just this morning. At 46, the Godfather of Punk looks more like the Godfather of Yuppiedom. And to think that this is the man who has spoon-fed us sex, drugs, and nasty-ass rock & roll since 1965 in songs like “Heroin,” “Venus In Furs,” “Walk on the Wild Side, “Berlin,” Metal Machine Music, for chrissakes! – and “Dirty Blvd.”; whose public brawls with the late rock critic Lester Bangs are now pop legend and whose influence on virtually all post-Seventies rock is indisputable.

“The thing about that comment,” Reed says of the heckler’s outburst at BAM, “is that if the guy had really been listening, I’m telling him something he doesn’t know. I’m giving him a side of Andy that nobody knows. But I was concentrating too much to respond. It takes so much concentration to do what I do. If I had let my concentration waver, it would have been too hard to get back into the piece.”

Such sound reasoning never stopped the Rock & Roll Animal before, but then the past is past, and Lou Reed and John Cale seem to be coming clean about it today. The Lou Reed who badgered a rowdy crowd at New York City’s Bottom Line on his 1978 Live: Take No Prisoners album is calmer today, taking his frustrations out lyrically on real enemies — like Ed Koch and the AIDS virus — and expressing in a charmingly awkward way his love for Andy Warhol. The John Cale who once smashed tables during a recital of modern musical composition, and cut the head off of a live chicken during a ’70s rock show — afterwards explaining to a group of vegetarians that “I didn’t hurt it, I killed it” — today mostly writes orchestral music, refuses even to use drums, and expends his leftover energy on the racquetball court.

Legend has it that Cale, Welsh-born and classically trained, and Reed, a Long Island kid who positively thrived on rock & roll, met at a party sometime around 1965. College-educated but streetwise, Reed had been writing churn-’em-out schlock pop songs for sleazoid businessmen at Pickwick Records in Coney Island, and Cale had been experimenting with minimalist drone sounds with the avant-garde composer, La Monte Young. Although it seemed an unlikely pairing, the street punk and the mad avant-gardist got on quite well. Cale had been moving away from classical music and was interested in combining experimental sounds and performance art with rock & roll. “In Lou, I found somebody who not only had artistic sense and could produce it at the drop of a hat, but also had a real street sense,” Cale says. “I was anxious to learn from him. I’d lived a sheltered life. So, from him, I got a short, sharp education.” On the other hand, Reed, idealistic and a bit naive, wanted to see rock & roll elevated to the status of fine art and literature.

In another part of town a shy and awkward Andy Warhol was working with a group of like-minded friends, duplicating familiar photographic images and calling it art, and experimenting with film, lights, music and dance, and other media. The bizarre goings-on at Warhol’s studio, the Factory, had become well-known to the art world; newspaper stories were being written, and the buzz on the streets was that these folks were wackos. All Warhol really needed to complete his multi-media extravaganzas, and become the world’s most famous living artist, was a rock band.

The Velvet Underground fit the bill, with their grinding and pulsating improvisational music. John Cale was at the helm, laying down thick slabs of bass and brushstrokes of droning viola; Sterling Morrison churned out blues guitar licks; Maureen Tucker pounded out simple, steady drum beats; and Lou Reed spouted street poetry. Warhol added the strikingly beautiful German model/singer Nico as a visual and sonic contrast to the chaos; she’d sing the soft, pretty ballads in a Marlene Dietrich monotone, while behind her the Velvets’ volcanic rumble always threatened to erupt. Warhol’s Velvet Underground and Nico would provide the focal point of his Exploding Plastic Inevitable multi-media parties. The band was shocking; Reed spoke frankly about violent sex at a time when “peace” and “free love” were the popular, more user-friendly slogans; about the horrors of heroin addiction to a generation which equated drugs with freedom. And all of this was bound by pure, noisy street skronk, at a time when the wind-chime sounds of the Grateful Dead were taking hippies to higher states of consciousness on another coast.

It’s 2 p.m. and raining bucketloads onto the thousands of umbrellas in midtown Manhattan, which, from Lou Reed’s 14th-floor vantage point, are making funny amoebic patterns as they siphon through the traffic. Right now, the traffic is at a standstill, and as the umbrellas wobble about, a cacophony of horns and sirens blares dissonance across the city.

“Whatcha smokin’ there?” Reed asks. Marlboros. “Can I have one of ’em?” Yes. “See, I’m trying to cut down with these Carltons, but I can’t resist when there’s, like, a real cigarette sitting right here in front of me.” He tosses the Carlton – off of which he has just broken the low-tar filter – into a clear glass ashtray, and then lights the ‘Marlboro.

In spite of his cleaned-up appearance and good behavior, Reed still personifies Cool. The immaculate threads are all black, the perfect ‘do is all black, and Reed is still as evasive as ever about his notorious rockstar life. With cocky facial tics and a wry tone, he refuses to comment on past comments, conveniently forgets specifics (“my memory is so bad, you know”), and changes the subject. He also makes some attempt to skirt questions involving emotion, but often winds up blurting out stuff like “I want people to like Andy Warhol” before catching himself. “I don’t wanna talk about the past,” he says up front, “I wanna talk about Songs For Drella. Okay? You can just say that John Cale was the easygoing one and Lou was the prick.”

“You can just say that John Cale was the easygoing one and Lou was the prick.”

JOHN CALE rests his elbows on a keyboard, which is connected by a spiderweb of coiled cords, via MIDI, to stacks of electronic equipment and speakers. The equipment is set up at the back of a mammoth rehearsal studio deceptively concealed upstairs at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Cale is wearing a V-neck sweater over a dress shirt, and a pair of faded blue jeans. His hair is cut short on the sides, with only one lock bouncing down over his boulder-like face. Cale stares up at the room’s high ceiling. He tends to get pensive when asked about his friends; right now, he’s thinking about the late Nico who, while bicycling with her son in Spain two years ago, died tragically of a heart attack. The muscles around Cale’s eyes tighten. “Nico,” he half whispers in his dampened, but still vibrant, Welsh accent. Then he pauses for a few long seconds. “Oh, I miss her a lot.”

Since the completed Songs For Drella closed at BAM in November of 1989, Cale has been hard at work here on his latest project, a piece called The Last Day On Earth. He is scheduled to perform it along with Bob Neuwirth at St. Ann’s, a beautiful Gothic church in Brooklyn, where an incomplete version of Drella was first performed as a work-in-progress in January of last year. All of Cale’s post-Velvets work has been like this: dissimilar, seemingly random. After he left the Velvets, Cale worked with an array of artists in various capacities. In addition to solo albums and concerts, he produced records by Nico, Patti Smith, Iggy Pop, and Jonathan Richman; performed with the likes of Terry Riley, Brian Eno, David Bowie, and Chris Spedding; he even did some unreleased session work with Gene Loves Jezebel. But he never again collaborated with Lou Reed. “Lou,” Cale says, again pausing to gather his thoughts, “Lou’s a difficult man to work with. But it’s rewarding.”

Properly titled Songs For Drella: A Fiction, the piece is a 15-song, hour-long musical dance through the life of Andy Warhol as Lou Reed and John Cale knew him. It isn’t exactly biography, but more like the kind of fiction that characterizes those morality tales based on the lives of great people who really lived (you know, like the story of George Washington and the cherry tree). Drella was subtitled “A Fiction,” says Reed, “so that if I decided to take poetic license with certain facts – like, did it really happen on 81st Street or was it actually 73rd Street – I wouldn’t have to be called into account for it. I don’t care about certain facts; if such-and-such happened before or after such-and-such, it makes no difference to me.”

Still, he feels that the “truth” in his “fiction” is at least as accurate as the “truth” in most of the Warhol biographies that have sold like hotcakes since the artist’s death in 1986. “I would say that Songs For Drella is very factual, but it’s fact communicated through fiction. Do you understand what I mean? There’s poetic license taken, and that being the case, I didn’t wanna be saddled with the burden of, like, this is a biography that is verbatim true. For instance, at one point John said to me, ‘You know, Andy did this record cover for me a few years ago (1972’s Academy In Peril) and it was in black-and-white. He told me that it would be worth more if I kept it that way. But I made him color it. I really wish I’d listened to him.’ I stuck that into one of the songs, and it gets a good laugh. And it’s true. But it isn’t true that it happened in a dream that I made up. So it’s fiction. You understand?”

Reed hopes that Drella (on Sire, and also available as a home video) will show Warhol as more of a three-dimensional man; more so, even, than the artist’s own diaries. More often than not, Reed speaks of the artist in the present tense. “The [Andy Warhol] Diaries are not a worthy epitaph by any stretch of the imagination,” he says. “At least for me they’re not. I think Andy is much more than that, and if you only look at that, you won’t get the full benefit of just what a unique and amazing individual he really is. What you experience through the record is the relationship between us and Andy. It’s not just about Andy; it’s not just, oh, he did this, he did that. When you experience Drella, it’s about John and me, it’s about me and Andy, and it’s about John and Andy. It’s a relationship. We want to make you know Andy Warhol better, make you feel him the way John and I feel him, so that you can experience the presence of this person and get closer to him. Anyway, I don’t know all that many people who’ll read The Diaries from beginning to end. And I don’t see why you have to have one or the other; you can have both, you know.”

The songs for Drella (a nickname that Warhol despised based on the combination of Dracula and Cinderella) are organized into a set of somewhat chronologically placed memories, historical facts, and anecdotes. It opens with the Warhol character railing about his youth spent in a small place where no famous people ever lived (“Small Town”), then moves straight to Warhol’s early days in New York, living in an apartment to which he would invite people for tea and chats (“Open House”). Next, the artist learns how to sell his ideas to people who have money to burn (“Style It Takes”). Warhol’s hardline work ethic, often touted by Reed in past interviews and songs, crops up in “Work”; his thoughts about art are spelled out in “The Trouble With a Classicist”; the artist’s love of the movies shows up in “Starlight”; his neuroses surface in, among other places, “Faces & Names”; his compulsion with photographic mass-production is seen in “Images”; and, in “Slip Away,” we see a disillusioned Warhol pondering over whether or not he will be forgotten when he stops his open-door policy at the Factory.

“It Wasn’t Me” is a biting defense of Warhol’s influence on his art groupies; “I Believe” is an all-out attack on Valerie Solanis, a psychopathic Warhol disciple who shot the artist in 1968, and, while not physically killing him, broke his spirit and marked the end of an era for Warhol and his Factory. Reed’s and Cale’s personal emotions and love for Warhol, qualities sometimes overlooked in the former Velvets’ past work, surface on Drella‘s finale, “Hello It’s Me.” The music, composed by Cale, is powerful, reminiscent of the Velvet Underground’s most intense moments, yet consisting only of Reed on guitar and Cale on synthesizer. Lou, who sings about two-thirds of the songs, wrote all of the lyrics. Most of them are patently direct, as obvious as the nose on Warhol’s face; though with their dry humor, along with Reed’s ironic vocal mannerisms, they’ll likely evoke pages of extraneous analysis. “It was a bitch to write,” Reed says. “There are all these conflicting emotions, all the way through to the very end.”

“It took some time for us to sort of break the ice, but it seemed the right thing to do to have us do something for Andy.”

Songs For Drella grew out of a couple of first-time-in-years meetings at Warhol’s wake. “At the funeral, Julian [Schnabel, the artist] suggested that we should do something for Andy,” says Cale. “I had been writing a lot of orchestral pieces as part of a symphony, and I felt that the music could be part of a requiem. So I said, ‘Yeah, let’s do a requiem.’ Then I saw Lou and it was the first time we’d spoke in quite a while. It took some time for us to sort of break the ice, but it seemed the right thing to do to have us do something for Andy.”

Says Lou: “At first, John and I got together and played just for fun, just to see if we would enjoy playing together again. And we did have some fun just doing stuff for ourselves. Then, at some point, he wanted a second opinion about this four-minute orchestral piece he had written. He’d been doing it with a computer – you know, MIDI. It was just a piano piece; four segments, about a minute each. He had a question about a melodic change he wanted to make, and he asked me if I would listen to it, and if I had a suggestion as to the way it might shape itself, you know. I gave it a listen, and then later he got in touch with me because he was thinking of expanding it into a longer piece. So he played this longer version for me. I said, ‘Well, you know, you could do this to it, you could do that, you could do blah-blah-blah.”

Meanwhile, Cale had been in touch with St. Ann’s, which, along with BAM, ultimately commissioned Drella. Then he suggested to Reed that the two of them write the piece together. “I thought it should be just songs,” says Lou. “I didn’t wanna have other musicians involved. John originally wanted to have strings and all, but I thought what would make the piece interesting would be just to have the two of us playing onstage alone. It would be more powerful that way. And, in fact, they commissioned us to do just that.”

“It was an important decision.” agrees Cale. “It put everything on us. It was really the best way for us to come out and perform and give people an idea of what was there in 1965, and what we thought was still there in 1989. So, what we ended up having was just the two personalities up there, and you could hear and see how the two related and interrelated and worked.”

In ten days, Reed and Cale came up with fourteen songs, consisting of made-up Andy Warhol dialogue, details about the Factory days, and personal memories. “It was done by osmosis,” Cale explains. “When we first sat down and started playing, there was this amazing energy – it was aggressive. We sat down and talked about all these memories we had, and then Reed shut himself in with a tape recorder running and showed up later with a kind of summation of what had happened. There were certain threads that ran through it which we had established, but it needed work. I was amazed at how much Lou let me into that process; you see, writing is such a personal thing for him. For him to let me be a part of going through all the lyrics and correcting was very difficult. We sat there and bandied them around. It’s difficult for him to collaborate on that level – it’s difficult for him to collaborate period. And he admits it.”

Cale and Reed tried out the songs on the St. Ann’s audience, while slides of Warhol’s art were projected onto a large background screen. But the climax of the piece, the glue that ultimately held the final version together, was yet to come. After the St. Ann’s gig, Reed wrote a dream sequence in the style of a short story (similar to ‘The Gift’ on the Velvet Underground’s 1968 White Light/White Heat LP). It would be read while Cale played slow, foreboding piano music with lots of warbling special effects. They wanted something that would give the final version of Songs For Drella a literary punch. The language in the piece, called “A Dream,” resembles that of The Andy Warhol Diaries, with Cale doing the reading, rambling Warhol-like about his day, his friends and ultimately, his death.

“It was John’s idea,” says Reed. “He had said, ‘Why don’t we do a short story like “The Gift?”‘ But then he went away to Europe.” Reed laughs. “He goes off to Europe saying, ‘Hey Lou, go write a short story.’ But I thought, no, not a short story, let’s make it a dream. That way we can have Andy do anything we want. Time and dimension and reality won’t matter, because it’s a dream. We could have him go anywhere, do anything, and not worry about facts. So, I thought this dream idea was the way to go. Let me tell you, man, it was really hard to do. But once I got into Andy’s tone of voice, I was able to write for a long time that way. I got to where I was able to, you know, just zip-zip-zip away – just because I really liked that tone so much. It’s certainly not my tone of voice at all. I really don’t talk that way. I had to make myself get into that way of talking.”

The dream moves along self-consciously, Warhol gossiping humorously about his friends, his magazine, Interview, his artists’ blocks, and his thoughts about the young graffiti artists and frisbee players he would see while strolling through Union Square Park. The tone is childlike; at one point, Cale, doing his best Welsh Warhol, blathers, “Lou Reed got married and didn’t invite me. I mean, is it because he thought I’d bring too many people? I don’t get it. He could’ve at least called. I mean, he’s doing so great. Why doesn’t he call me? I saw him at the MTV show. He was one row away and didn’t even say hello. I don’t get it. You know, I hate Lou! I really do!”

“It’s not like, ‘I fucking hate Lou Reed… It’s more like (he puts on a whiny, sing-song voice), ‘Oh, I hate Lou; oh no, I reeeeally do.’ “

“That was a very important line,” says Reed. “When John was doing the reading, I kept telling him that when we get to that line, ‘I hate Lou,’ you gotta say it like a kid. It’s like the way a little kid would say it. It’s not like, ‘I fucking hate Lou Reed, I really hate that son of a bitch.’ It’s more like (he puts on a whiny, sing-song voice), ‘Oh, I hate Lou; oh no, I reeeeally do.’ You know? It’s all in the nuance, and that’s why the production both during the performances and on the record was so critical – especially on that cut. If you just read it, you could say it a whole number of ways. And you’ve also got to be careful what effect you put on the voice. I mean, if what you’re wanting is the emotion out of a certain line, then you’ve got to place both the effect and the word right with the music so that you hear it just the right way, so that you give the listener the best shot at hearing it the way it’s supposed to be. You do it wrong, and it just ruins everything; if it isn’t together you miss the nuance and everything’s lost. But if you say it the right way, it’s funny. And that’s how it came across in the performance” — he knocks on the hardwood desk — “thank God.

“There are other places in the piece where we were supposed to get a laugh, and we did get it during the performances. If it hadn’t have come across, it would have been a little disappointing. But that sort of thing’s happened to me before. Of course, on record you never know what’s going to happen. For the first time, I understand why they have those background laugh tracks on TV. Because on a record, you’re on your own; you don’t have an audience. Some people might say, ‘Gee, what’s this mean?’ So it’s important in the production that you get the nuance in the voice – and that the nuance is the right one in the first place – so you can get a laugh from it. I mean, the thing is awfully funny until the last paragraph – then it takes a real turn.”

At the end of “A Dream,” the Warhol character sees his death. “I wanted it to have a solid ending,” says Reed. “If it didn’t take that harrowing turn at the end, it could have just gone on forever, you could have just arbitrarily stopped anywhere. I mean, you’re writing, and you have to find some kind of ending – you know, a real punch, a wind-up, some kind of emotional thing – to make it satisfactory as a piece of writing. That’s why it had to take that turn. If it hadn’t taken that turn, it could’ve been three minutes long, it could’ve been 30 minutes long; because it’s just building this personality on you, and you’re laughing, and you’re kind of liking this guy. You’re almost forgetting that it’s Warhol, and you’re just liking this guy who’s saying this stuff. He’s funny, and he’s kind of interesting, and then all of a sudden – WHAMO! And, of course, what I’m talking about there is true.”

In the song, Reed traces Warhol’s death back to the Solanis shooting. He also makes this suggestion in the song “I Believe,” where he says, “Not until years later would the hospital do to him what she would not.” On this point, John Cale parts company with Lou. “When Andy died, I personally never felt that it all went back to the shooting incident. His death seemed to me to just be one of those ridiculous bits of human theater.” Another inflammatory statement in the song was: “I believe life’s serious enough for retribution/I believe being sick is no excuse/I believe I would’ve pulled the switch on her myself.” Cale has problems with this as well. “I didn’t really feel that we should have gone after Valerie Solanis in quite that way; to have said that someone deserved the death penalty.” However, Cale says he reads the line as more of an emotional reaction than a political statement. “I mean, that’s a very fine line, I suppose, but I do think that…[long pause]…it was just a very dramatic way of saying something about – I don’t know – something you feel on an emotional level. I don’t think that you can really discern a murderous frame of mind there.” Reed maintains that his writing speaks for itself.

Andy Warhol had a profound impact on the lives of Cale, Reed, the other members of the Velvet Underground and just about everybody else who frequented the Factory. Years after the media glitz, Velvets guitarist Sterling Morrison commented that “on reflection, I’ve decided that he was never wrong.” Warhol repeatedly prodded the cast of characters at the Factory to think in novel terms, to continually come up with new ideas; he staged wild publicity stunts, and he always stressed the value of maintaining a healthy work ethic. In “Work,” another song reminiscent of the Velvets in its unbridled tension and steady industrial grind, Reed sings, “No matter what I did, it never seemed enough/He said I was lazy, I said I was young/He said, ‘How many songs did you write?’/I’d written zero, I lied and said ‘ten’/You won’t be young forever/You should have written fifteen/It’s work, the most important thing is work.”

Reed shuffles in his chair, thinking of his own recorded output since leaving the Velvet Underground. “It’s not nearly what it should be,” he says. “And that’s me talking, not Andy – well, I know what Andy would say. He’d say what I’m saying, and it’s true. It’s not remotely what it should be, and that’s something I’m trying to do something about today. An album a year or every two years isn’t really that much. But, you know, you can’t really do all that much more with records because it’s hard to conceive of putting out two records a year – they’re hard to write. But there are other things that I should be doing that involve writing – more than what I’m doing now.”

REED TAKES great pains in Songs For Drella to defend Warhol against the bad press he’s gotten over the years – particularly the assertion that the artist had a guru-like effect on his followers. In “It Wasn’t Me,” the Warhol character cries, “I never said give up control/I never said stick a needle in your arm and die…You act as if I could’ve told you, or stopped you like some god/But people never listen and you know that that’s a fact…I never said slit your wrists and die/I never said throw your life away…You’re killing yourself – you can’t blame me.”

Reed comments, “You’d have to be in Andy’s shoes before casting the first stone, and I don’t think that you or anybody else has ever been in those shoes. What was he supposed to do? Have a little counseling session for 30 people? I mean, like, everybody was free, white and 21. If they had been looking for counseling, they wouldn’t have been there, right? Anyway, he did make suggestions. Suppose I say to you, ‘Oh, don’t do that. That’s really bad,’ and you don’t listen to me. Have I fulfilled my obligation? Well, he did that a lot. I don’t think it’s fair to put such a burden on him; I mean, it’s not a case of ‘the Lady doth protest too much.’ Besides, talent can be very attractive and seductive, which is what I was getting at in ‘Style It Takes.’ That’s a seduction song. And ‘Work.’ That’s Andy talking; those are verbatim quotes. Now, if that doesn’t come under the heading of good advice, I don’t know what does.”

Cale says that his greatest advice from Warhol was to anticipate potential artistic roadblocks, and to keep reaching for the stars. “When we met Andy, we already had a work ethic,” he says. “Andy showed up after we’d worked on the banana album for nine months. Every week we had spent our entire weekends going over and over and over and over the songs until we had wedged some new arrangements onto, like, ‘All Tomorrow’s Parties,’ ‘Venus In Furs,’ ‘Black Angel’ and ‘Heroin.’ We had no big problem with the work ethic; in fact, we were hanging on to the work ethic for dear life. Andy taught us that if you have ideas about what you want to do in rock & roll, then you’re going to have to figure out what problems you’re going to be facing as fast as possible. Andy was a co-conspirator in that sort of thing. He also helped us do just what we wanted to do by keeping at us, pointing us further out, further out, and further out.”

Call and Reed recalled that advice during the Songs For Drella collaboration. “In order for things to happen like that again between Lou and me, we had to go through that same sort of process; we had to play these things over and over just like we had in the past. And we did that. But this time we kind of knew what the landscape would look like, we were prepared for those things that we needed to be aware of – the distractions and stuff.”

Some of the embers left over from the fire that scorched the bridge between Cale and Reed back in the ’60s were still warm – even after the Songs For Drella project was completed. “Lou felt that I didn’t appreciate how much effort he had put into the words. He never actually said this to me personally. The comment was made to a lot of other people.” Cale pauses, looking downward. “That was a shocker; it’s very difficult to fight with, or argue. If someone thinks that you really don’t appreciate what they’re doing, well then what can you say? It’s just a very sad and disappointing turn of events. I mean – and whether you actually base it on anything substantial or not – it’s just the clincher.” To rectify Reed’s apparent self-esteem problem, Cale wrote in the liner notes: “Songs For Drella is a collaboration, the second Lou and I have completed since 1965, and I must say that although I think he did most of the work, he has allowed me to keep a position of dignity in the process.”

Reed takes a very long draw from his cigarette, smashes it out in the ashtray, and frowns. “I really don’t wanna get into that kind of thing,” he snivels. “I just wanna talk about the record. That thing he wrote says what it says; it says Lou did the majority of the work. That’s that. I very much like playing with John. He’s a very exciting musician. It’s fun playing with him. We play very well together. John is enormously technical, and everything’s got to be set up just right in the studio to make it happen with the least amount of problems. I like that.”

“Lou was exorcising a lot devils back then, and maybe I was using him to exorcise some of mine.”

Cale adjusts himself in his seat, and stares forward. “I think what happens is that there’s some kind of… envy that goes into this sort of process. Envy that’s somewhat self-generated. I don’t know what the reason for it is. There just seems to be something that builds up over a long period of time that eventually, hopefully, will go away, be forgotten. There’s a certain vortex that builds up between two people who are very similar; I think that maybe it’s peculiar to people who are very similar in nature. I mean, I can’t exactly claim to be pure as the driven snow.”

Cale brushes back his hair with one sweep of his large, construction worker-like hands. He looks up again, toward the rehearsal room’s high ceiling. “When I first met Lou, we were interested in the same things. He had certain expertise in songwriting that I thought was absolutely amazing. We both needed a vehicle; Lou needed one to carry out his lyrical ideas and I needed one to carry out my musical ideas. And that’s where it all ended up, that sort of gnawing, or whatever it was we were doing. We didn’t know it at the time. I mean, I was going off into Never-never Land with classical notions of music. All we had was a backbeat, and Mo would hang onto that; Sterling would be playing blues guitar, and Lou would be changing personalities and stuff – like, one minute he’d be a preacher and the other he’d be a… he’d be a poet. Lou was exorcising a lot devils back then, and maybe I was using him to exorcise some of mine. So, when we first started working together, it was on the basis that we were both interested in the same things. That was why the Velvet Underground was put together. That’s… that’s why we got together this time around.”

© Mark Kemp, 1990

Watch Lou Reed perform “The Goodbye Mass,” from his 1992 concept album Magic & Loss:

[youtube width=”640″ height=”480″]http://youtu.be/g4oggz_nWvg[/youtube]

That’s a wonderful look inside one of my very favorite records in the world, and one I especially appreciate today.