Less than a year after the suicide death of Kurt Cobain, I saw one of his favorite bands, Meat Puppets, perform at a big Christmas party in Los Angeles. I’d seen them many times since the mid-1980s, and they sounded great, but there was turmoil all around them. Seven months later, I flew out to Arizona to meet up with Meat Puppets’ singer and guitarist Curt Kirkwood, and talked to him about the state of his band and of rock music, post-Nirvana. The Meat Puppets had recently appeared on Nirvana’s swan song, MTV Unplugged in New York, a stroke of luck that suddenly thrust them into the spotlight of mainstream rock. Though I wasn’t aware of it at the time, Kirkwood’s bass-playing brother, Cris, was headed down the same harrowing road that Cobain had been on before his death. Kirkwood alluded to his brother’s problems, seeming to speak directly to him in some of his comments to me about Cobain. (Cris would go on to experience some even lower bottoms due to his drug use, eventually serving time in prison for an event involving a Phoenix security guard.) The atmosphere was tense in Curt Kirkwood’s home on that hot July day , but my story on him and his band remains one of my favorites from the 1990s. It speaks to the discomfort of a generation of musicians who didn’t ever expect to gain mainstream acceptance.

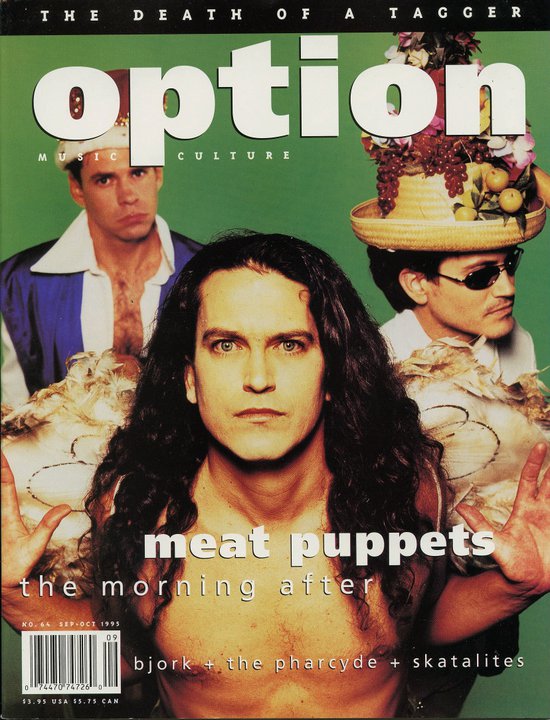

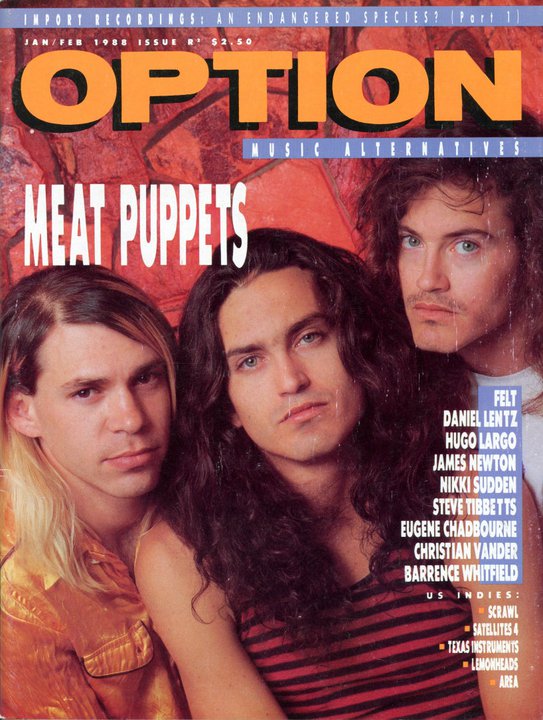

These scruffy indie champs did nine albums and more than a decade on the road before a longtime fan, Kurt Cobain, turned them into stars. Now, Arizona’s favorite psychedelic punks are basking in the mystery of it all.

By Mark Kemp, Option, September 1995

It was like a mirage. The Meat Puppets ambled onstage at the KROQ Christmas Party last December, and nearly every member of the largely teenaged crowd inside L.A.’s Universal Amphitheatre knew who they were. The audience went wild when the band tore into its runaway hit “Backwater,” singing along to every word. After 15 years of what the trio’s punk-rock peer, Mike bassist Watt, calls “econo touring,” the scruffy Meat Puppets had become overnight pop stars.

It’s not something they’re complaining about.

“I fucking love show business,” growls Curt Kirkwwod, the band’s singer, songwriter, and guitarist. “So many people in this business don’t like it. They whine about their success. They get addicted to drugs. They just aren’t happy with what they’ve done.” He pauses for a bong hit. “I don’t know what to say to them: ‘Why’d you get in a band, then?'”

MESA, ARIZONA. High noon in late July. A stuffy 115 degrees outside. Kirkwood is sitting at the table in the air-conditioned dining room of his two-story home, sucking on a Heineken and reloading his bong — a 32-oz. Gatorade bottle with a pipe stem jammed into its side. His girlfriend, Sandy, is stooped on the floor in a semicircle with the band’s manager and sound man, kicking their asses in a game of rummy. Elmo, Kirkwood’s 12-year-old son, is sequestered in the living room in a bundle of blankets, watching Scooby-Doo on TV. Kevin, a brawny, brown-and-white English pit bull, has his two front paws in my lap and is vigorously licking my face. George Jones is on the boom box crooning “Why, Baby, Why?”

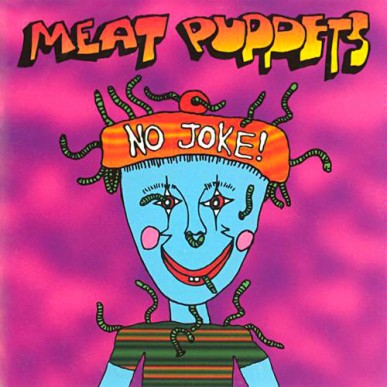

The Meat Puppets have just finished recording No Joke, their third album for London Records and the follow-up to the trio’s surprise hit of last year, Too High To Die. That’s the record that put the long-struggling cult band over the top, selling 500,000 copies — more than all of the Pups’ previous nine albums combined — on the strength of “Backwater.”

And then there’s the Kurt Cobain connection. In 1993 Nirvana invited the Meat Puppets along for their In Utero tour. Later that year, when the band appeared on MTV Unplugged, Cobain sang three songs — “Plateau,” “Oh Me” and “Lake of Fire” — from the Puppets’ 1983 album, Meat Puppets II. After Cobain’s suicide in 1994, DGC released the acoustic set as MTV Unplugged In New York. The album has since sold 3 million copies, and its residuals have made the Meat Puppies — which also include Kirkwood’s bassist brother, Cris, and drummer Derrick Bostrom — wealthy men.

Kirkwood takes another hit from the Gatorade bottle. “For me, in terms of what I feel about myself, not much has changed,” he says, exhaling a stream of sweet-smelling smoke. “I know who I am, and that’s all that matters to me.” Wearing a white, V-neck T-shirt and faded blue jeans, Kirkwood looks like your average working-class hippie in his mid-30s. His wavy brown hair is tied back in a ponytail, and his pretty-boy features are beginning to show signs of wear and tear. “The way I look at it is, I fucking caused whatever happened to us with Nirvana,” he continues. “They chose to have us come along with them, but I wrote those songs.” He pauses and stares blankly at the wall behind my head. “I don’t know why things happen,” he says in a near whisper. “I have thought a lot about it — why? why? — but I don’t know.”

Long considered one of the sexier denizens of the underground — he was recently interviewed by the saucy Playgirl magazine — Kirkwood is getting a bit of a middle-age spread: his gut is thicker, and his jaw is not as square as it used to be. But his icy, blue-green eyes are still as piercing as ever. “This new audience of younger kids is like a vacuum,” the 36-year-old guitarist continues. “They don’t know what the fuck they want, but they know they want something. And if they want anything I’ve got to offer, cool.”

The big question for the Meat Puppets now is whether their newfound popularity was a fluke. No Joke will determine that. It’s the Puppets at their most bone-crunching, experimental, and melodic. From the squalling lead guitar that introduces the first track, “Scum,” to the breezy country-rock of “Chemical Garden,” the album is one seamless aural facsimilie of the band’s distorted observations of humanity. Cellos, piano and chiming acoustic guitars play alongside feedback, the Kirkwood brothers’ tangled guitar-bass interplay, Bostrom’s deceptively simple beat, and lines like, “Under the stones/We find the scum/Under the stars/We find the scum.”

“I’m not discounting humanity because I feel like we’re scum; it’s not a derogatory thing,” Kirkwood protests. “To me, it’s just fucking reality.” Brother Cris sees the Puppets’ Dali-esque musical landscapes as a kind of mirror image of society: “We’re just a little channel for the horrors of the world.”

CURT AND CRIS Kirkwood are true children of the American Southwest. Their Catholic parents, Vera and Don, met at the University of Nebraska in Omaha in the late 1950s, and married when they learned Vera was pregnant. In 1958, the couple moved to Wichita Falls, Texas, where Curt was born the following January. They didn’t stay long. In 1960, Don, an Air Force man, moved the family west to Amarillo, where Cris was born that October. Three years later, the Kirkwoods were back in Omaha when Curt, then 4, had to undergo surgery. That’s when the family started falling apart. “I had a kidney removed and I guess it was just too traumatic for my dad,” Kirkwood says bitterly. “My parents divorced right after that.”

Vera briefly moved the boys to Acapulco, Mexico, where her father had made millions in the hotel business (she was later cut out of the family forture). By Curt’s second year of school, the family had moved again, to Phoenix, where Vera married a horse racer named Paul White. “He was a total cowboy from Golden, Colorado,” Kirkwood recalls. “He wore big cowboy hats and linen shirts.” The family settled into a red-brick, ranch-style house in the city’s Sunny Slope neighborhood, which at the time was a rural area out on the northern edge of town. By 1970, when Curt was 11, his mother had divorced again and married a “rowdy fucking crazy man who liked Bruce Lee movies and was interested in literature about the Third Reich,” Kirkwood says. The man wound up nearly burning down the house.

Curt and Cris began looking for an escape. The elder brother turned inward. “Before I was 8, I believed in elves and things,” Kirkwood says. “When I discovered they weren’t real I started looking into the origin of the myth. My mom always told me, ‘You have a good imagination, you should use it.’ So that became my world. My imagination is as real to me as anything. ” He liked music — the Monkees, the Beatles, Bobby Sherman — and his favorite TV programs were the Glen Campbell and Johnny Cash variety shows. But his real passion was motocross bikes. “Racing motorcycles was my life until I was 17,” Kirkwood says. “It was my outlet. It was a major part of both Cris’s and my world.”

For Cris, motorcycles were just something Curt had introduced him to. “Like a lot of little brothers, I followed him into the things he found cool,” Cris says. “He got into motorcycles, I got into motorcycles. I loved it, but what I really loved at the time was playing my banjo.” Cris had discovered bluegrass when he saw the movie Deliverance. “I was a fat little boy,” he says. “That was something I could do by myself.”

When an accident ended Curt’s motocross career, he began focusing on guitar. After a semester of college in 1977, he dropped out to become a full-time musician. “I’d become kind of an outcast, which was something I could do to replace the bikes,” he says. “I was really fucking flipped out.”

Kirkwood wasn’t the only one feeling that way. The ’60s were seven years dead, and a growing segment of his generation had decided that the disco, soft-rock and arena sounds of the ’70s were not addressing their rage. The Sex Pistols’ first album landed on U.S. shores the year Curt dropped out of school, and Derrick Bostrom, a new friend from the upper-middle-class neighborhood of Paradise Valley, was trying to persuade the Kirkwood brothers to get with the program.

Bostrom’s family was unstable too, but nothing like the Kirkwoods. Born in Phoenix, in 1960, he was raised in a liberal intellectual environment. When he was 6, his parents divorced, and his medical technician mother, Sandra, remarried a doctor. Derrick and his brother, Damon, spent their teenage years living with his family in a sprawling, ’70s-style home with a guest house and huge saguaro cacti in the front yard.

Bostrom was an excellent student at Chaparral High, where, as editor during his senior year, he turned the school paper into a sort of National Lampoon. “I was a straight-A student, a pothead who had the longest hair in school, and I ran the paper,” recalls Bostrom, as he takes me for a ride around his old neighborhood the following day. “I had more fun that year than I’ve had at any other time in my life.”

His mother and step-father divorced in 1979, two years after Bostrom had turned the Kirkwood brothers on to the Pistols’ “No Future” — and right about the time the three decided to form a band. “I was able to get them somewhat interested in punk rock,” Bostrom says. “Curt had been in a few non-punk bands and kept getting kicked out because he was too wild. I thought, let’s harness some of that wildness.”

The Kirkwoods were still living at their mother’s Sunny Slope home in 1980 when the Meat Puppets recorded their first EP, the feral In A Car. On it, the band buzzed through five twangy, avant-hardcore songs in just five minutes. It was the Puppets’ ticket into the fledgling punk scene. After a few gigs in the nearby college town of Tempe, the band took its show to Los Angeles. Their unlikely mix of desert weirdness and hardcore spirit so impressed Black Flag guitarist Greg Ginn that he asked the trio to do an album for his new label, SST. The Puppets’ raucous, self-titled debut was the label’s third full-length release, behind the Minutemen’s The Punch Line and Black Flag’s Damaged. It wasn’t until Meat Puppets II, however, that the band perfected its blend of punk energy with country-rock melodies and experimental, Jerry Garcia-like noodling. Music journalist Kurt Loder gave the LP a four-star rave in Rolling Stone, which, until then, had rarely covered the indie scene, let alone given one of its bands such high praise.

Right around the time Meat Puppets II came out, Kirkwood’s twins, Elmo and Katherine, were born to his then-girlfriend, Cinda. “Our lives were so fucked up,” he remembers, shaking his head. “We were into all kinds of weird shit. We were so young. A lot of the stuff on that album has to do with having kids. It was weird, because when I wrote the song ‘Split Myself In Two,’ we had no idea we were going to have twins.”

FOR THE NEXT DECADE, the Meat Pups were on a long, strange punk-rock trip, getting fucked up as often as possible, touring with little money, and watching the wheels of the indie rock scene gain momentum. The band’s audience expanded with 1985’s Up On The Sun, which added progressive rock and jazz-inspired moves to the sweet, country-folk melodies. They cranked up the volume on 1987’s Huevos in homage to ZZ Top. The indie-rock faithful couldn’t figure it out: Had the Meat Puppets sold their souls or was their collective tongue buried deeply into their cheeks?

By the late ’80s, the Meat Puppets had seen some of their fellow indie bands, such as Hüsker Dü, make the big leap to the majors. “We weren’t ready,” Kirkwood says. “Nobody would be ready until after Nirvana. Time has fucking made itself very clear. That’s why they call it Father Time and Mother Earth. There are things in this world you gotta be respectful of.”

The Meat Puppets’ pre-Nirvana major label debut in 1991, Forbidden Places, was the trio’s first with an outside producer. But Pete Anderson, a guitar virtuoso whose specialty is his pristine production work for country artists, wasn’t well suited to the Puppies’ ragged sound. “I think we just decided to go with the flow on Forbidden Places,” Curt says. “We thought: We’re capable musicians and we’re artists, so we can do this. I did my best on it, but I think it would have been a better record if it had been a little less thought out.” He pauses, looking down at the lighter he’s fiddling with. “Maybe some of the songs were a little tedious, too. But it was hard going from a cult band to a major label, because the majors don’t care about your cult status.”

Pete Anderson “had a certain way of going about it, especially in the area of mixing and getting vocals on tape, which was a serious waste of time and effort and energy for us,” Bostrom says. The band’s next album, Too High To Die, proved to be a giant leap forward, thanks in part to the production of Butthole Surfers guitarist Paul Leary. “When we started working on Too High To Die,” Bostrom says, “it was largely about finding a producer who wasn’t going to do to us what Pete Anderson did.”

While major-label bureaucracy loomed overhead, Kirkwood was involved in another layer of business with SST. The Puppets had never signed a contract with their former label, but they wanted to gain control of their earlier albums and publishing rights. “I just had a gut feeling that my songs would be valuable some day, and I was right,” Kirkwood says. “I’m goddamn lucky that I got them back when I did, ’cause right off the bat, we got this things going with Nirvana which happened to be really popular. How did I know that would happen? I didn’t. But it happened as soon as I fucking resolved that situation.”

Curt and Cris Kirkwood both have a hard time using words like grateful — unless they’re referring to the Dead — but you can see the gratitude in their faces as they shrug their shoulders. “At that fucking point in my life, for Kurt Cobain to come from out of nowhere… I mean, I had no fucking association with the guy, none whatsoever, until —BOOM! — there he was,” Curt says. “When you’ve been dogged all your life, and all of a sudden some little champion comes through for you…” He trails off, then continues, “I don’t know what to say. I wish my thoughts could come out more completely.”

Cris puts it this way: “Before that shit happened, I thoroughly figured it was going to be Burger King for the lot of us for the rest of our lives. I’ve been pretty blown away by the whole thing. I mean, we were always heralded by the geek patrol — big deal.”

After Cobain’s death, the Pups were dogged by questions about the impact of the singer’s suicide on them. “I don’t think anybody has any idea what Kurt Cobain meant to me,” Curt says. “To this day, I’m completely fucking disturbed by what happened. And yet I totally understand it. I feel it more than I understand it. I don’t have any questions about it. I’m disturbed because I can’t speak my mind about it the way I’d like to; I can’t feel the way I want to feel about it, because we live in such a fucking weird society that I don’t think my point of view would be nurtured.”

Kirkwood alludes to those feelings in “For Free,” a song on No Joke. “It’s just a fuckign disclaimer, basically,” he says. “The title says it all. It’s not really for Cobain, per se. I did it because I’ve known a lot of people who’ve killed themselves in the name of this fucking garbage scene” — he spits out the word like poison — “and I think that’s such a shitload. I didn’t take Cobain to be some kind of huge icon. To me, he was just a person I worked with. That’s a rarity for me, because one of my icons is work. And when you spend time working with somebody like him, well, that shit’s fucking cool, man. It’s totally real.”

THE WALLS of Curt Kirkwood’s home are adorned with his own twisted, soft-colored paintings: a portrait of a death-blue Lincoln with a tiny log cabin in the background; the earth colors of the coffee mug that graces the cover of Up on the Sun; the Aztec-like bird from Out My Way; and other canvases populated by the grotesque and the distorted. Right now, Kirkwood is sharing a moment with his son. The two are flipping through a fanzine-like booklet called Bostrom’s House of Horrors, a collection of grisly photographs the drummer culled from the Internet, of people who died violent deaths.

“Hey, Dad, look at this one,” Elmo says, a shit-eating grin on his face.

“That’s cool,” Kirkwood responds, “check this one out.”

For some punk-rock veterans, looking at corpses might be just another dated pose. But I get the feeling that Curt Kirkwood is searching for something beyond the corporeal — his sickness is almost spiritual. Having been through so much upheaval in their lives, both Curt and Cris are intensely distrustful of humanity. While listening to “Scum,” Curt says, “That’s a beautiful song, isn’t it? It’s like, ‘What are we?’ I certainly don’t know. And I don’t care. I don’t have a dream for people to be anything other than what we are. But I do like the idea that there’s a perfect person out there who we can hold a candle up to. I hope to meet him some day.”

Kirkwood distances himself from the idealists of rock’s past. “I’m the exact opposite of John Lennon,” Curt says. “To me, there is no hope. I love what John Lennon did. He plumbed to the depths what he could about humanity in the early ’70s. But I don’t agree with him in any way. I don’t think human beings exist in the way John Lennon imagined them. I think this world is total fucking slime. It’s a fucking human sewer — and I love it.” The statement doesn’t seem so contradictory when he later tells me that all things “just burn into love at a certain point.”

None of the Meat Puppets harbor any lofty visions of humans working together for the betterment of themselves or the planet. Bostrom laughs. “People don’t take well to our ideas, which are just this side of the militia mentality,” he says. “We don’t espouse kind, compassionate things. We’re not really into the whole white-man’s liberal guilt trip. And we’re not all that worried about righting the wrongs of oppression. I mean, why try to save a sinking ship?

“Personally, I’m more into concepts,” Bostrom continues. “Freedom. Enlightenment. And I’m more interested in one-on-one relationships than in saving the whole of humanity. I guess I’m basically an anarchist.”

For Curt, it’s a loner’s philosophy. “I don’t have many people around me,” he says. “I keep my family close by” — he waves his hand around the dining room — “the people you see right here.” It’s about midnight now and Elmo is running around the house, dancing wildly to the Ministry disc that Curt just plopped into the boom box. “My kids are the best thigns in my life,” he says. “You can’t get any closer to a person than that. They’re the excuse I have for being fucking semi-normal after all I’ve been through.”

He smiles. “I try to stay normal. I’ve exorcised many demons through this music and I’m still pretty fucked up,” Curt says. “I’m real volatile. I’m unpredictable, a total nuisance, really hard to get along with. But I’m a lot better than I was 15 years ago.”

© Mark Kemp, 1995

Click Part 1 and Part 2 to check out a Behind the Music-like account of the Meat Puppets rise, fall, and return. Then check out this killer performance from the band’s mid-’80s creative prime: