This was my very first music story for an alternative weekly. I was covering an all-ages hardcore matinee featuring three NC bands for The Spectator of Raleigh, North Carolina. In talking to the guys in the bands, I got the impression that they felt they weren’t getting the attention they deserved compared to other, more indie-friendly Southern bands of the period — like R.E.M., Fetchin Bones, Pylon, The Connells, and Southern Culture on the Skids. As it turns out, the ultra-DIY hardcore scene was getting plenty of national attention. They had their audience — it just wasn’t being written about in Spin or Rolling Stone. I learned later that the characters in this story weren’t thrilled that I identified them as “feeling left behind.” C’est la vie. Also, in re-reading this piece 37 years later, it occurs to me that I must have been mad at R.E.M. for some reason, because I alluded to their sound when describing what COC and their ilk don’t sound like. (Sorry, Michael.) Please pardon the cliched similes and incorrect use of a word or two (I crossed out the most egregious instance) — I was 24 and stupid.

Corrosion of Conformity, Ugly Americans, and Subculture get no respect

By Mark Kemp, Spectator Magazine, 1985

It seems ironic that two of the loudest, most prolific, and most politically vocal bands on North Carolina’s so-called new music scene represent a silent minority, shunned as if they were the black sheep of the South’s new musical family. It’s a predicament rock & roll often gets itself into: Bands once considered counterculture start bobbing up and down at the surface of the pop-music mainstream, leaving their more unfashionable friends behind. Despite the notable advances they’ve made on the national music map, Corrosion Of Conformity and Ugly Americans feel left behind.

These Triangle-based groups don’t sing about nice things. They don’t ramble philosophically about lost harbor coats or the tranquility of finding one’s way in the Blue Ridge Mountains. Instead, they point their fingers at social violence and government intervention in Third World political struggles. They don’t weave their vocals into layered circles of guitar, bass and drums, creating musical paintings whose merits can be judged from a studied, artistic point of view. Rather, they thrash out simple, loud-fast metal guitar riffs that knife their way into the listener’s subconscious.

They don’t create perfect pop nuggets that can be placed neatly into rock & roll pigeonholes, to be categorized and examined. No, their songs burn with anger and frustration, and the band members themselves say they could care less about rock & roll genres. COC and Uply Americans churn out rapid-fire rock songs as if the very future of the human race depended on them. They growl their lyrics like mongrels howling from a dog pound. And while their music consists of a lot of overdriven, heavy-metal-style riffage, the song structures are decidedly punk.

A good many N.C. bands tread the waters of the new music mainstream these days, content to play roles in the scene, willing to bend with prevailing styles. But the decadent hardcore boys aren’t looking to join the mainstream. For years, they’ve held their ground, fighting like Doberman pinchers to avoid it — or at least to ignore it. And now they feel abandoned by the movement. “We’re not in that clique,” says COC drummer Reed Mullin. “We weren’t accepted in it.” Ugly Americans singer Simon Bob Sinister agrees. “I don’t see us in that at all,” he says. “But it’s not that I’m opposed to it. We’re more willing to see ourselves as a Southern band than they are willing to accept us as that.”

COC singer and bassist Mike Dean explains why they’re not a part of the hype. “When people regard something as unpleasant, they usually don’t want to deal with it,” he says. “I believe that’s why we’re separate from the [local new music scene]. But we don’t want to put anybody down because of it.” Even though the bands might seem a bit disenchanted, they fight hard for respect. “We’re very serious about what we do,” Sinister says. “At least we do tour, and we dedicate a lot of time to it.”

Mullin and Sinister have helped push the local hardcore scene into national repute. They each produced their bands’ own albums for nationwide release on an independent California label, Death Records. The two also work together to organize national tours, and they help budding hardcore bands break into the business.

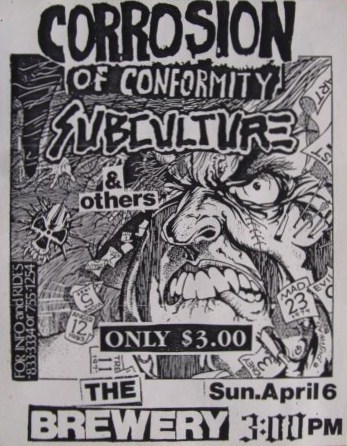

IT IS WITH SUCH STAUNCH determination that on Sunday afternoon, April 6, in spite of what Mullin and Sinister might see as a lack of support from the regional mainstream indie scene, the two staged a hardcore matinee show at Raleigh’s Brewery. It featured Ugly Americans, COC, and a younger sibling band from Winston-Salem, Subculture. They rented the club for $200 and charged their devoted followers $3 to get in the door. No alcohol was allowed — just energy — and the event was open to all ages.

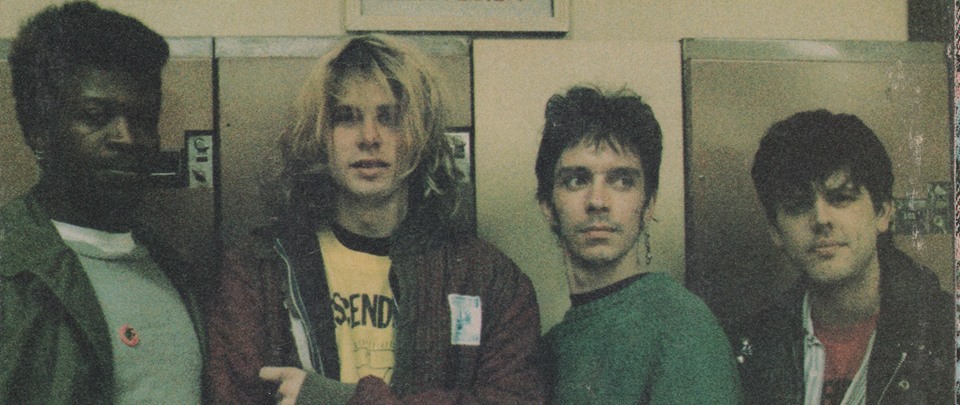

“These are the three best bands in North Carolina,” 20-year-old Mullin boasted at the onset of the show, combing a hand through his mop of long blond hair. Scattered across the Brewery’s bar was an array of hardcore fanzines, including Ink Disease, an L.A.-based underground rag, and Guillotine, a neatly packaged punk zine from New York. Some of the fanzines featured articles about the North Carolina thrash bands. T-shirts were hung for sale on a wall behind the bar, and records were sold from beneath the counter. It was a perfect display of the hardcore scene’s grassroots approach to music.

Subculture kicked things off with a headbanging set that throbbed like a cross between Ratt and the Ramones. Fronted by adolescent shrieker K.C., 18 years old and still wearing braces, the band plays songs that are short bursts of metallica, most of them marked by quick tempo changes and simple, half-step chord progressions. “We would play heavy metal if we could,” scoffed guitarist Matt Smart Ass after the performance. “It’s just that it’s obvious we’re really not that good. I’d say we’re probably at the very bottom, talent-wise.” Clearly, Smart Ass’s name fits him well.

Subculture is also the least political of the three bands, their forté being the frustrated-teenager-bitches-about-life-in-general approach to rock & roll. For example, in “Le Chartier’s Principal,” K.C. screeched, “I’m tired of waking up from a sleep / That’s my only peace /To have to face this mess again and again? / Someday I hope it will all end.” Then he charged into the refrain: “Faster, faster, you gotta keep movin’ / All the time I’m losin’ and losin’ / Striving for a goal you tell me is there/ Well, maybe I don’t even care.”

Ugly Americans — Sinister and guitarist Danny Hooligan, with substitute drummer Mullin and utility bassist Mark Ussery — displayed a deeper, more ominous stage presence than Subculture. The group is very political, but vocalist Sinister and the boys also seem to relate to the frustrations of adolescence, and they come off like big brothers with advice for their younger siblings.

“I’m going to get preachy now,” said Sinister, who resembles David Lee Roth in ultra-fast motion. “We’ve done something down in Nicaragua called wage war. Now, if you’re stupid enough to go in the Army and support that, you’re stupid enough to suffer.” After the band finished its set, Sinister explained that he directs such messages to a small but significant group of enlisted men who have adopted hardcore as an outlet. “These skinhead guys in the Army think hardcore is cool because they think it means violence. But it doesn’t mean that at all. It’s more like a release of tension. Slamdancing is healthier than, like, fighting in the street. I’m not saying that it doesn’t sometimes get out of hand, but it doesn’t usually.”

“These skinhead guys in the army think hardcore is cool because they think it means violence. But it doesn’t mean that at all. It’s more like a release of tension.” — Simon Bob Sinister

In the song “Buffalo Billy and His Wild Rodeo Show,” Sinister, a vegetarian, growls, “I give you a hero who slaughters and maims / Who raped this country and thrived on its pain / I give you the death of an entire species / And the senseless extinction and its worthless glory / With a pistol in holster and a rifle at side / On his prize-winning stallion, on his long, hard ride / To kill every buffalo he sees through his sights / And to laugh at the carcass in bloody delight.”

Next onstage, COC singer and bassist Mike Dean screamed into the microphone, garbled vocals full of demonic-sounding venom, knotted dreadlocks bouncing up and down in front of his face. Behind that threatening stage presence, Dean is anything but sinister. “Hardcore to me is liberating,” he said. “It provides a good, healthy disrespect of authority. We really want to try to encourage kids to know what our government is doing, to know what its motives behind foreign policy are. I think the motives are profit, power and influence at all costs, just to keep the Russians out.”

In “Intervention,” while guitarist Woody Weatherman and drummer Mullin thrash behind him, Dean growls, “American dollars and weapons gleam / Support another corrupt regime / Human rights long out of style / Another killing another farce trial / Intervention.”

Dean believes that hardcore straddles the fine line that separates heavy metal and punk, although he claims he does not like metal’s sexist outlook. He also says he doesn’t like the new music mainstream’s refusal to face up to society’s problems. Perhaps it is that frustration that makes hardcore a mutant sibling of both the mainstream new music scene and heavy metal, and perhaps that’s why local hardcore bands like COC and Ugly Americans feel they have been cast out of N.C.’s musical Garden of Eden.